Tomorrow, three years and two days after the day that Ireland voted “ta” to the prospect of gay marriage, another referendum is scheduled. What is before the voters this year, in the Republic of Ireland, is the repeal of the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of the Republic of Ireland. It prohibits abortion. This all goes down tomorrow, May 25 (or today if you’re in Ireland. As I write this, it’s 6:59 in the morning. The polls open in less than one minute.). Time is of the essence: history is being made, and I must race ahead of it and the outcome and collect my thoughts.

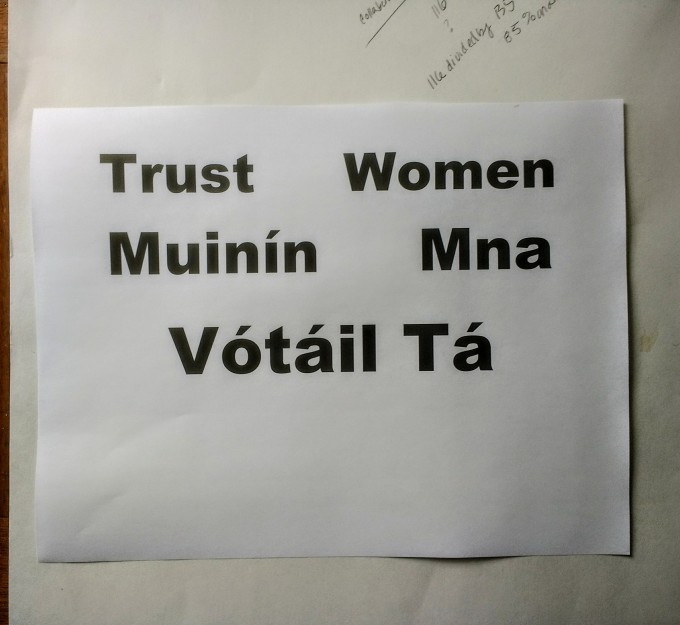

I took BART to SFO today to join a courageous woman named Krista who decided that what she should do was hold a sign at Gate 91 in SFO’s International Terminal, applauding the Irish who were flying home on the once-a-day direct flight to Dublin to cast their vote. She showed up two days before the referendum, holding a colorful sign that read “Thanks For Flying. #hometovote. Trust Women”.

“I don’t know what the regulations in the airport are, but I figure if I stand here, out of the way, it’s ok,” she told me. Krista has direct brown eyes and confident bearing and I think Hannah Sheehy Skeffington, my favorite Irish revolutionary feminist, would be really impressed with her. I was. The reaction, she said, had been very positive. “A lot of young men, who are flying home to vote, stopped and shook my hand and thanked me. Lots of young women, certainly, but a lot of young men. Old and young alike.” Her favorite, Krista said, was an older man, using a walker. “He gave me a wink. He stopped pushing his walker, gave me a wink, and carried on.”

Two men walked past us twenty minutes later, both in their sixties. One of them snapped a picture of us on his cell phone, and told us we were doing a good job. After that, two women stopped to talk to us. Their names were Mary and Maura. They, too, were older. “We’re for repeal,” Maura said simply.

The Amendment they wish to rid themselves of was inserted into the Irish Constitution in 1983, and is, as activist Janet Ní Shuilleabháin has been explaining all around the county for the last few years, a carryover of the days when Ireland was a British Colony and had the “Offenses Against the Person Act” in their criminal code, which prohibited both queerness and abortion. (Janet pointed out in a Facebook post that this was the act that was used to prosecute Oscar Wilde. )

This act was taken up within the Bunreacht na hÉireann immediately after the 1922 Civil war. Contraception was banned in 1935, and both these expressions of fearful contempt were followed by articles 41.2.1 and 41.2.2, authored by the Taoiseach of the time, Eamon De Valera, which legally confined women to the home in pursuit of preserving the family as the “natural and fundamental primary unit group of society.”

This was called “fascist” by Sheehy-Skeffington in a letter she wrote to Prison Bars, a news sheet started by Maude Gonne: “Never before have women been so united as now when they are faced with Fascist proposals endangering the livelihood cutting away their rights as human beings…” She and other Irish revolutionary feminists launched a campaign to have the articles deleted from the draft constitution, and replaced by language from the 1922 constitution, which affirmed the equality of all citizens “without distinction of sex”. They lost. The Constitution and the articles within—which lurk inside the Constitution to this day—came into force in December of 1937, setting Ireland down a dark path of a punishing and insular conservatism that was followed closely until pretty fucking recently. Read this letter from Academics For Repeal, an Irish organization of in 103 academics, in support of repealing the 8th. It lays this history all out.  I was remembering all of the above history today, as I greeted the Irish who were in full #hometovote mode. Aoife Caulfield, who was wearing a Repeal sweater, stopped to take our picture and talk with us. She had radiant blue eyes, which welled up with tears as she explained what this moment meant. “It’s great that I’m going to be home tomorrow to cast my vote,” she said. “It’s so emotional.” Her voice caught and she cried openly for a second. “It has to pass.” She allowed that she was worried.

I was remembering all of the above history today, as I greeted the Irish who were in full #hometovote mode. Aoife Caulfield, who was wearing a Repeal sweater, stopped to take our picture and talk with us. She had radiant blue eyes, which welled up with tears as she explained what this moment meant. “It’s great that I’m going to be home tomorrow to cast my vote,” she said. “It’s so emotional.” Her voice caught and she cried openly for a second. “It has to pass.” She allowed that she was worried.

“I’m from Clare, and my mom said no one is talking about it. It’s like people are afraid to bring up the topic in conversation. It’s the rural areas that are the worry. But then I think maybe people are secret “yes” voters! And that they’re just afraid to come out and voice their opinion.”

That wouldn’t be surprising. Secrets, lies and silence: the tight gag of place. I heard all about this coping strategy, this tradition of non-disclosure and the famed Hibernian chattiness that disguises it, from Dr. Ruth O’Hara, another Irish feminist, who taught classes in the Irish Studies Program at the New College of California, in the nineties, when I was a student. Ruth, who was a Stanford professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in her spare time, delivered lectures on the arc of Irish history, and gave particular emphasis on the development of women’s roles, or lack thereof, after the Irish Civil war and the disastrous 1937 Constitution. It was not a hopeful history at all. Frankly, it was very bad.

Ruth told us about the offending Constitutional articles, the introduction of the Eighth Amendment and what it all meant and the horror that these ideas caused: the banishment of women from the economic and political sphere, the introduction of unforgiving and brutal social mores that penalized women with institutionalization, and confinement in the Magdalene Laundries. I heard about the laundries and the situation at Tuam in Ruth O’Hara’s classroom on Valencia street in 1999, years before the graves were “discovered”. I heard about and read accounts of the suicides of women and girls who got pregnant and saw no way out.

I was told about the “X” case. I knew about the girl in the graveyard, bleeding out next to her dead infant son. Whatever you say, say nothing,” said Ruth, quoting Seamus Heany. This is how it is, she told us, this is how women’s lives are handled.

The passing of the Eighth Amendment, a desperate and nasty attempt to prevent Ireland and Irish woman from benefiting from legal abortion, cannot pass out of the Constitution quickly enough. History will (I think) show that ultimately all the strictures placed on women got dismantled, but this is cold comfort. The history that led to the repeal of the Eighth will still have to document and contend with hundreds of years of a grossly unjust, terrible past; one that involves millions of women traveling to Britain to obtain a legal abortion, and darker stories too, social ostracization, terrible shame, terrible fear, just animal terror.

There isn’t enough space in this blog post to talk about the terror of living in a society where you have no control over your body, the same body that comes with a full suite of sexual and reproductive capacities. These histories, colonial and post-colonial, form a dreadful geas, a series of conditions and taboos that doomed Irish women, who fell afoul of them.

Taboos are meant to be broken, they say. I think this particular taboo will be thoroughly broken tomorrow. Today in the airport, women wearing “Repeal” sweaters rushed past, pulling their luggage behind them. They looked over at us, and smiled at our signs, giving us a thumbs up. They were individual parts of a mighty diasporic stream, going back to Ireland to vote and change the future of their country, something that was impossible to do, 160 years ago, when my family like so many others, had to leave knowing that they’d never see the place again. A woman named Grainne walked straight over to us. “I have to take your pictures,” she said and did. She started crying and held up her arms for an embrace. We crowded into it and held on tight.

Finished and posted at 7:41 a.m., Irish time.

With forever love to my darling Lizann, my beautiful friend, whose light will never dim.

#RepealedtheEighth

#Repealedthe8th