Part Two: The Great Glanders Epidemic of 1892

To return to the story of Edward John Creely: prior to his involvement with tubercular cows, he may have been briefly employed by the industry that created them. In 1890, a “J Creely” appears as a “dairyman” working at 35 Eddy Street, in a building known as Washington Hall. It housed the retail offices of three dairies, the Guadeloupe, San Mateo and New York Dairy, the latter owned by scofflaw dairyman George Smart, who would go on to poison the Lent children after selling their mother milk adulterated with formaldehyde in 1905.

There’s no proof that “J Creely” was Edward Creely, but it probably was. Industry regulators often find work as the employees of industries they later regulate (or fail to.) There was also more than one J. Creely in the city. Creely, his father and brother all had the same initials (Edward Creely was christened John Edward.) To avoid confusion, he swapped out his first name for the second throughout his professional life. But in any case, Creely père and frère were too busy to take up sideline gigs as a dairymen. Edward wasn’t. In 1890, Edward, who started his college studies at St. Ignatius College, finished them as a veterinary student at the University of New York. He returned to San Francisco, where highly-trained veterinary surgeons were in demand.

Creely didn’t linger at 35 Eddy street for very long. As the son of a horseshoer, horses were what Creely knew, and horsepower was what the city ran on. San Francisco had hundreds of horses on its payroll. In the 1891-92 San Francisco Municipal Report, the fire department reports having 88 horses scattered among its 34 stations, and a hostler and veterinary surgeon on staff to tend them.

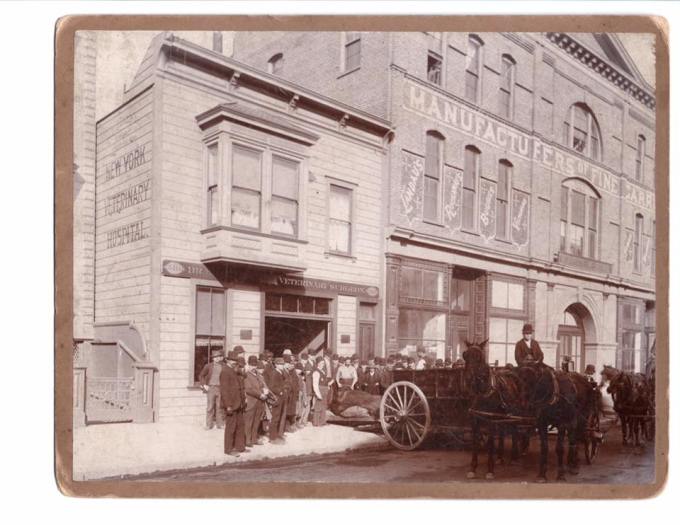

By 1891, Creely had opened his first establishment, which catered to horses. Called the New York Veterinary Hospital, it was located at 510 Golden Gate Avenue, and was one of several veterinaries that stretched along the avenue from Hyde to Webster Street. Isaac O’Rourke, who specialized in equine dentistry, was located at 331 Golden Gate Avenue, followed within one block by F.A. Nief at 434, Creely at 510, and Ira Dalziel at 605. The “San Francisco Veterinary Hospital” was the last of the bunch and lay the furthest west at 1117, close to the intersection of Golden Gate and Webster street. This hospital was owned by William Egan and Peter Burns. Egan was Creely’s landlord and owned the property at 510 Golden Gate. Both Egan and Burns would later become antagonists of Creely.

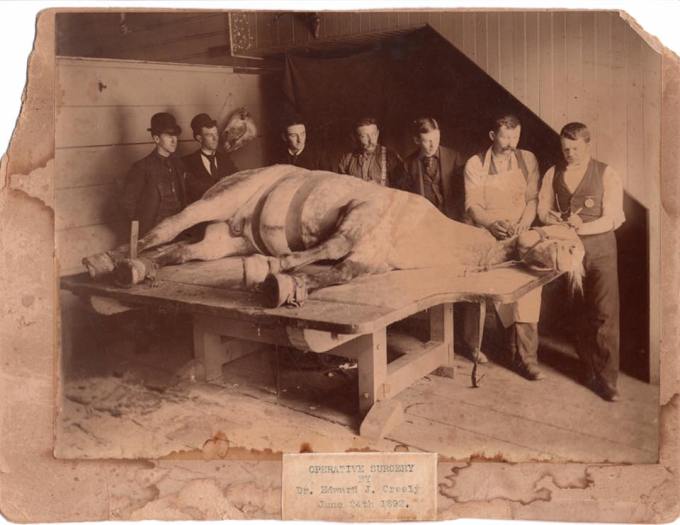

The first announcement that the New York Veterinary Hospital was open for business ran on January 24, 1891 in the Pacific Rural Press, a paper for farmers and agricultural businesses in California. Seven days later, Dr. Creely made the news for his feat of fitting a draft horse suffering from ocular cancer with a glass eye, earning the gratitude of the horse’s owner, Le Roy Brundage, who didn’t want to lose the entire animal for the lack of an eyeball.

Uncle Edward who boasted of a state-of-the-art facility with steam baths for the hard-working horses of the city, kept upping the ante in the highly competitive world of veterinary surgery. In 1893 he saved a choking horse by inserting (he used the terrible word “ramming”) a teakettle spout into the horse’s trachea. The spout was later replaced with a conventional breathing tube. This got him some media attention, and an offer to become a columnist for the Pacific Rural Press.

“Of Interest to Many Readers: Beginning with the first issue in October, the Pacific Rural Press will furnish a veterinary department, which will be in charge of Dr. E. J. Creely, D. V. S., of this city. Any questions relative to diseases of cattle and horses, stock, hogs, poultry, etc., will be answered promptly and intelligently, the idea being to furnish free information to our readers that will be of value to them.”

The ledes in his column read like the titles of penny dreadfuls: Mare With Mysterious Trouble, Crack In the Frog, Cows Killed By Ergot, Treatment for Nasal Gleet in Horses, and Glanders and Farcy and How To Detect Them, among others.

But the attention he received from the press wasn’t always positive. A year before his promotion to veterinarian-at-large for the readers of the Pacific Rural Press, Creely created some bad press for all the right reasons, namely glanders, an infectious and ultimately fatal disease caused by a bacteria called Burkholderia mallei.

Glanders attacks a horse’s respiratory tract, and first appears as a foul discharge leaking from the nostrils. If the horse is not destroyed, the disease migrates to the skin, causing subcutaneous ulcers to develop. At this stage the disease is called farcy.

Glanders is floridly disgusting, and easily preventable by providing humane living conditions for horses, which were hard to come by for the 18th-century urban horse. Horses pass it among themselves when squeezed into crowded stables like the St. George livery on Bush street, which stuffed as many as 150 horses within as little as 5,200 square feet. This gets a horse about 35 square feet, which is very little. A moderately proportioned horse needs at least 60 square feet to fit comfortably into a horse trailer.

All this infectious proximity came with a human cost as well. Glanders is a zoonotic disease; it jumps from horses to humans with ease. No human was known to have died from glanders in San Francisco when Dr. Creely offered a startling observation free of charge: glanders, he said, was at epidemic levels in San Francisco, killing horses, and maybe humans, too.

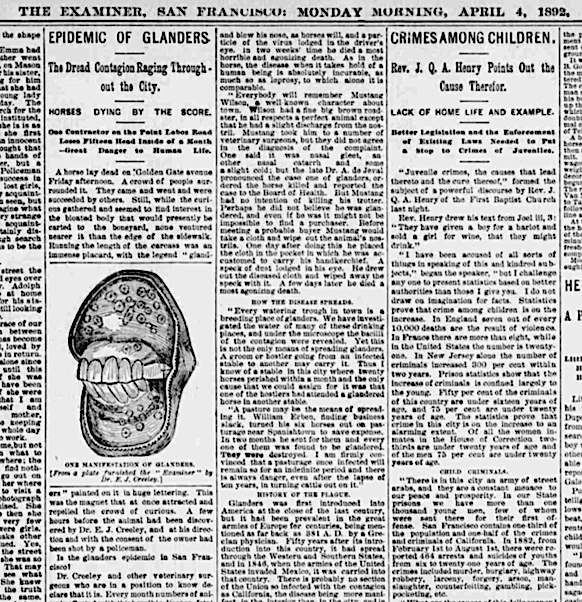

The lede in the San Francisco Examiner on Monday morning, April 4, 1892 couldn’t have made the stakes much higher.

“EPIDEMIC OF GLANDERS: The Dread Contagion Raging Throughout The City. Horse Dying By The Score.”

The story started with a dead horse, dumped in front of Creely’s surgery, with a placard attached to its neck, reading “glanders”. The placard might have been an attempt to comply with city ordinance no. 1880, which advised horse owners with that they must place a bright yellow placard, the color of caution, around their horse’s head to warn others that the stricken animal should be avoided. (This measure was mostly ignored.)

The Examiner reporter called to the scene asked an obvious question to Dr. Creely, who at the age of 25, was probably the youngest practicing veterinarian on the avenue. Was there an epidemic of glanders? In the article that appeared a day later the Examiner stated that Creely and “other veterinary surgeons who are in a position to know” thought there was.

“The public do not understand the great risk they are taking handling, being around or even driving behind a glandered horse,” asserted Creely, before going onto name two individuals who he claimed died from glanders: a man with the colorful nickname of “Mustang Wilson”, as well as the Sheriff of San Jose who died after his horse tossed his head, and his infected snot, in the sheriff’s face.

“There is scarcely a livery stable in the city that is free from it,” concluded the Examiner, in an unattributed quote, that nevertheless was understood to have come straight from the horse’s mouth, Dr. Creely, the only veterinary surgeon willing to be quoted by name.

The allegation that public liveries were hotbeds of infectious diseases resulted in a flurry of articles in the Call, the Examiner and the Chronicle. Although the story ran almost ten years before the bubonic plague arrived in San Francisco, the city was used to being sickened and killed by their living conditions. A “dread contagion” was not only plausible, it was half expected.

Liveries were the mobility business of the day, providing last mile, and longer, transportation solutions to San Franciscans. The allegation that they were responsible for spreading glanders sent shock waves up and down Golden Gate Avenue, which was home to the aforementioned cluster of veterinarian hospitals as well as several public liveries. All of these establishments existed within one square mile of each other. By today’s Google reckoning, walking from the first livery on the avenue—Crittenden and Bailey’s stable at 24 Golden Gate Avenue– to the last, Charles F. Robinson’s livery at 1212 Golden Gate Avenue, wouldn’t take more than 22 minutes.

This is the very definition of a tight-knit community: proximity and mutual dependence. Charles Taylor’s livery stable at 310 Golden Gate was located directly next to W.H. Carpenter’s (later Isaac O’Rourke’s) veterinary surgery. This symbiotic pattern of livery stable interwoven with veterinary establishments made pragmatic sense—having a vet nearby is a bonus, as anyone whose been awakened at 3 a.m. by a sick cat will tell you—but the street pattern undoubtedly incubated a political culture that had implications for the regulatory aims of the city. The co-mingling of vets and livery owners had the potential, and the profit motive, to hold health reforms hostage to baser concerns.

Golden Gate avenue with its hundreds of horses may well have been a hot zone of infection. From 1891 to 1892, 11 glandered horses were recorded in the city’s official municipal record as having been destroyed. But the avenue was probably also prone to outbreaks of professional censure, slanderous gossip and petty corruption as well. William Egan, Creely’s landlord and competitor, sarcastically refuted Creely’s claims of a looming epidemic in an article in the San Francisco Call on April 7.

“(I) say without hesitation that it is ridiculously and grossly exaggerated and full of misstatements,” said Egan, going on to draw a fine distinction between contagious disease and an outright epidemic. Glanders, he said, was only contagious, and could only be spread through contact with the “glandinal” discharge of a horse. The bacteria wasn’t airborne, he claimed, and therefore lacked the power to spread as widely and quickly as epidemics spread.

Egan claimed special insight into the situation due to the fact that he was on the payroll of at least seven city liveries, St. George’s among them. He saw no conflict of interest in using insider knowledge to downplay the story and chose, instead, to cast doubt on the whole affair by calling out Creely, whose youthful “inexperience” was derided as mere ignorance. He was joined in this by several other veterinarians, who also had business arrangements with city liveries. All of them warned of the panic that Creely’s comments were creating. Owners were reportedly already removing their horses from public liveries.

The controversy also threatened to derail a hotly anticipated city event: the thoroughbred horse race slated to take place that month at the Bay District Racing track in the Richmond district. Hosted by the Pacific Coast Blood Horse Association, the city was welcoming wealthy men and their expensive steeds just as the story broke. The owners, who had spent thousands of dollars on their thoroughbreds, were thoroughly freaked out at the prospect of stabling their investment next to glandered horses. There was big money –$1,900 was collected at the gates–and social status at stake. Senator Stanford, James Fair and W.H. Crocker were expected to attend the race, as well as experienced turfman like Creely’s uncle, the famed horse trainer Daniel “Whitehat” McCarty, who was planning on racing his two-year old filly “Bridal Veil”. All of this sporting glory was being jeopardized by Creely’s comments.

On April 12, an apology, so penitent as to be slightly craven, appeared on page 7 of the SF Call from Creely to the community of angry livery owners, and veterinary surgeons. “He is not responsible …for the assertion that glanders was raging in the livery stables. Quite the contrary, the doctor does claim that the livery stables are the last place in the world to find a case of glanders..” The apology hit most of the three “R’s” now in wide use. It responded to the growing enmity expressed by his colleagues, expressed regret that he had said it (although he stuck to his story that he hadn’t said it) and assured the readers of the SF Call that it would not happen again. The last claim wasn’t true.

In June the imbroglio reached its apex. Creely announced in the San Francisco Chronicle that he would seek twenty thousand dollars from publisher W.R. Hearst for libel, saying that the statements supposedly “emanating” from him had not, especially the claim that public liveries were menacing equine and human health. Creely said (and this is the only part of the whole affair which is undoubtedly true) that the story had “injured” his reputation and profession. He was referring to his professional community, clearly, but his family must have said something. Whitehat owned three liveries at various times in San Francisco, and was in the brutal business of racing horses. Creely’s father occasionally sold horses, too. But of those admonitions, nothing remains but speculation.

In any case, Creely’s public shaming was short-lived. By the following year, he had a column in the Pacific Rural Press and he was still being consulted by the Chronicle, who were trying to figure out how much of a threat glanders really posed. In January 1893, a man died from glanders in Los Angeles. Creely repeated himself. “It simply adds force to the warning which everyone who drives horses or takes care of them should heed against exposing himself to an animal who has this contagious malady. There is nothing more dreadful than death from glanders.” That April, Creely was appointed to the position of the city veterinarian, for the princely sum of 40 bucks a month, over the objection of Peter Burns, William Egan’s partner at the San Francisco Veterinary Hospital, located down the avenue.

All in all, the episode looks like a monumental miscalculation that backfired. What motivated Creely to make his claims? There are no recorded human deaths from glanders since the Health Office (later the Department of Public Health) began reporting deaths in 1865 in the city’s municipal reports. Was the dead horse a publicity stunt gone wrong? Were his accusations an ill-conceived attempt to knock out the competition? Or was Creely telling the truth?

If so, then the tragedy of the deaths of all those horses, who with magnificent necks, flaring nostrils and impenetrable dark eyes, carried the city’s business on their backs and or pulled it behind them, was deepened by Creely’s failed attempts to do the right thing. He may have tried to put public health on an equal footing with pecuniary considerations, and raise the alarm around the hazard that unregulated stables and liveries posed to the health of San Franciscans. He may have begun his career with the best of intentions. But in a city surrounded by equally ambitious men equally capable of corruption, his good intentions might not have mattered.

Creely prospered, despite two high-profile incidents of petty corruption in 1896 and 1909. He not only managed to secure a series of city and state offices; he’s credited for founding the second veterinary educational institution in California. The University of California opened their college first, on the northwestern corner of Post and Fillmore in 1896, later moving to U.C. Davis. On April 28, 1899, Creely, Mulford Pancoast, H.M Stanford, Joseph Sullivan, and John Murray filed articles of incorporation with the state, which officially founded the San Francisco College of Veterinary Surgeons and Dentists at 510 Golden Gate.

There’s nothing remotely horsey about Golden Gate Avenue now: the 1890’s are too long ago in geological and urban redevelopment terms for any trace of the community of veterinarians and stable owners to remain. The 1906 quake and fire destroyed it. After the earthquake, Creely moved his hospital/college to 1818 Market. In 1915, he announced plans to build a new college on 10th near Stevenson, but that building never materialized and the college closed in a few years later. This may have had to do with his advancing age– he was 50, an age that was sometimes fatal for Creely men– and the fact that horses were vanishing from the city. The resonant clopping of their hooves on the macadamized streets was being replaced by different sounds.

The site where the first hospital and college stood now hosts the American Academy of English. The only image that remains of the New York Veterinary/San Francisco Veterinary College is a picture of Creely standing on top of the building in June of 1906. He’s either in the process of cleaning up, or re-building in the aftermath of the disaster that leveled his competition, and reshaped the city he lived in.

Office of Dr. E.J. Creely, first veterinary hospital in S.F. June or late May, 1906. Golden Gate Ave. (#510), near Polk. Creely is barely visible on the roof of the building. From the California Historical Society, and available at the Online Archive of California

Office of Dr. E.J. Creely, first veterinary hospital in S.F. June or late May, 1906. Golden Gate Ave. (#510), near Polk. Creely is barely visible on the roof of the building. From the California Historical Society, and available at the Online Archive of California