(NOTE: This is an essay I wrote on St Patricks Day in 2017 and posted on Medium, and am reposting here four year later. LookHuman still have really stupid tee shirts for sale, but not the tee shirt discussed below. )

This month, Irish America was alerted to the fact that LookHuman, an online retailer based in Columbus, Ohio, had created a special tee-shirt for St. Patrick’s Day with the following message: “My potatoes bring all the Irish to the Yard. And they’re like that famine was hard”. I looked at the shirt, and wondered how much anger (and I got some: outrage is a natural resource I’m rich in) I should expend. I have to pick my battles. There’s no shortage of bullshit in America these days and the badly punctuated meme-shirt was so loutish, and stupid that it was hard feeling anything other than scorn.

It’s seasonal, this outrage. It starts in February when retailers start selling their supremely crappy St. Patrick’s Day-themed merchandise. Cinco de Mayo gets it just as bad. As soon as we get clear of the green-tinted juggernaut that is St. Patrick’s Day, shirts with messages like “Keep Calm and Swallow the Worm” or “Drinko de Mayo” will become available.

I was familiar with LookHuman’s meme-y-merchandise because their shirts were being worn at the Women’s March in San Francisco. So how did this company get from Feminism to Famine? Why did someone think of combining Kelis’s song of sexual confidence with the worst disaster ever to befall Ireland? Did some designer, high on the reality of living in a Trumpian world, decide to design the most offensive tee-shirt they could think of? That’ll teach those dead people to whine about their lack of food! And what, pray tell, does LookHuman’s stated mission of giving “everyone the ability to express their passions, personalities, and identities, no matter what kind of nerd they are” mean? Are Famine nerds a thing?

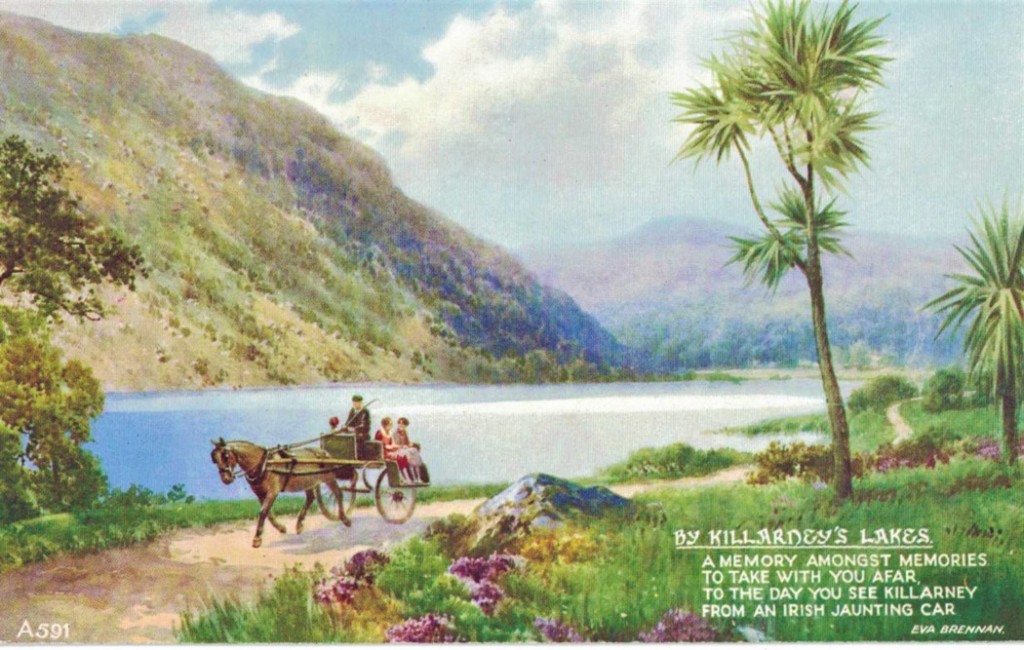

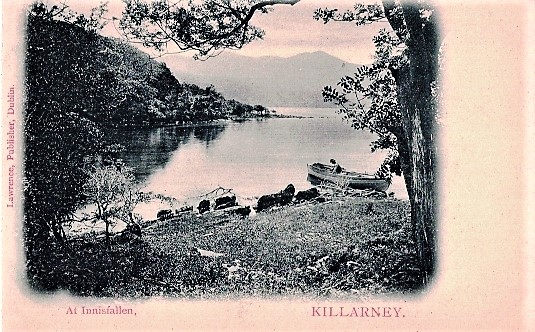

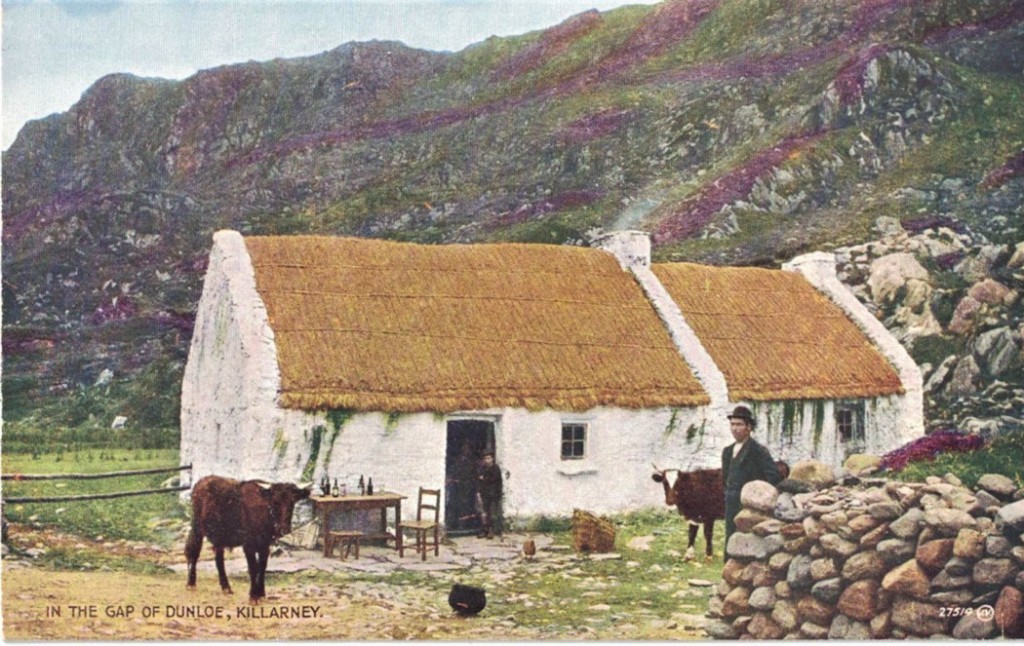

Not so coincidentally, my friend Vicky had given me a pile of vintage St. Patrick’s Day-themed postcards a week earlier, and in the aftermath of the Famine/Milkshake shirt, I developed a new-found respect for the artisanal quality of the postcards and their messages, which wished good things for people, like health, wealth, and safety. Among the cards were several ink-tinted images of the lakes of Killarney that were printed around the turn of the 19th century. I squinted at the tiny words printed on the margin: “Lawrence, Publisher, Dublin”, it read.

“Lawrence, Publisher” turned out to be an entrepreneur named William Mervin Lawrence, who was born in the GPO and opened a photo studio on Sackville Street opposite his birthplace in 1865. Lawrence hired a photographer named Robert French, who took nearly 30,000 images of Ireland, mostly landscapes, from about 1870 to 1910. French retired in 1914. Two years later, the events of the Easter Rising destroyed Lawrence’s studio and the images that were stored there. Thankfully, most of French’s landscapes survived, having been stored offsite.

French, a Dubliner, knew his country well. The Lakes of Killarney were a perennial favorite in cities like San Francisco, which hosted many immigrants from Kerry. French took full advantage of the landscape in Killarney, and the lakes that thread their way between the valleys. One postcard, entitled, “At Innisfallen”, shows a classic composition: the drama of the landscape and its lake is offset by a fisherman sitting quietly in his boat, near the shore. It is very peaceful.

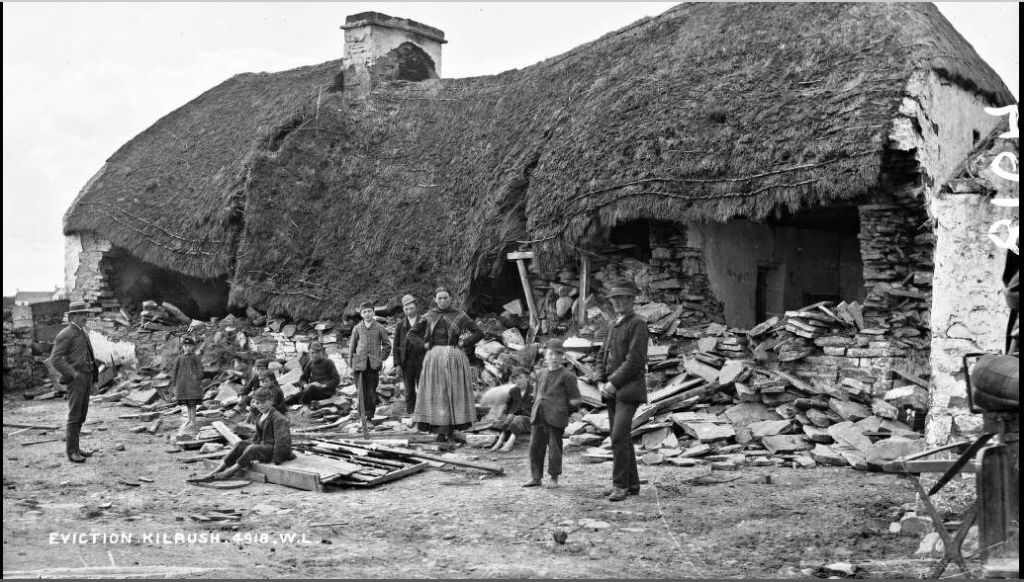

French also took pictures of other things. “Eviction Kilrush” is the name of a picture he took in County Clare in July 1888. On that day, the cottage of Matthias McGrath was destroyed by a battering ram wielded by agents in the employ of McGrath’s landlord, who wanted to “clear” his estate of tenants. McGrath was evicted, and his family arrested for resisting the eviction process. “Eviction Kilrush” is one of a series of photos that shows evictions in County Clare during the Land Wars, a roughly thirty-year period of agrarian resistance. The period was defined by the struggle of Ireland’s tenant farmers to rid themselves of landlordism, the system by which the land of Ireland — and the lives of the Irish who depended on that land — were held in the grip of absentee landlords.

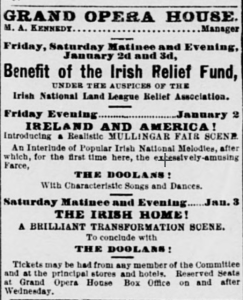

The Land War is a thrilling episode in Irish history and if you don’t know anything about it, you should. In comparison to earlier, unsuccessful movements for national sovereignty, the Land War is notable for its success. In his book “Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World“, Marxist historian Mike Davis lauds Michael Davitt, a supremely humane man with one arm, for his brilliance in organizing Ireland’s tenant farmers, many of whom only narrowly survived the famine. Davitt, and his champion in Parliament, Charles Stuart Parnell, launched the movment in 1878 in County Mayo, Davitt’s home county, with meetings between Davitt, Parnell, sympathetic clergy and tenant farmers. They organized tenant farmers into a sustained and disciplined movement that fought for and won the Three F’s: Fair Rent, Fixed Tenure and Freedom for the tenant farmer to sell his interest in his holding. In San Francisco, it was a popular cause: fundraisers were held at the Grand Opera House and local branches were quickly formed. Branch Number 1 of the Irish National Land League held a meeting in October of 1881, raising $136 dollars, which would be about $4,000 today.

From the Daily Alta, December 31, 1879: advert for a benefit for the Land League.

This wasn’t enough to help the tenants in County Clare. By the time French showed up with his huge camera and supply of glass plates, 200 tenants of Captain Hector S. Vandeleur who had been negotiating for reduced rent for over a year recived eviction notices. Later, the battering ram was dragged from cottage to cottage as the land clearances on Vandeleur’s estate began in earnest on the morning of July 18. Twenty-two people were evicted from Kilrush, and their homes destroyed. “Eviction Kilrush”, “The Battering Ram Does Its Work” and other pictures he took that day immortalize the abuses of the landlord system in Ireland, and depict very clearly what was at stake during the land wars. French’s attitude towards the brutal evictions he witnessed aren’t made explicit in the curatorial notes that accompany the images, which are held by the National Library of Ireland. But his photos show how picturesque ruins get made. Entire communities got disposed of, leaving destroyed cottages behind, which lived on in 20th-century postcards as symbols of Olde Ireland, in craggy, picturesque landscapes.

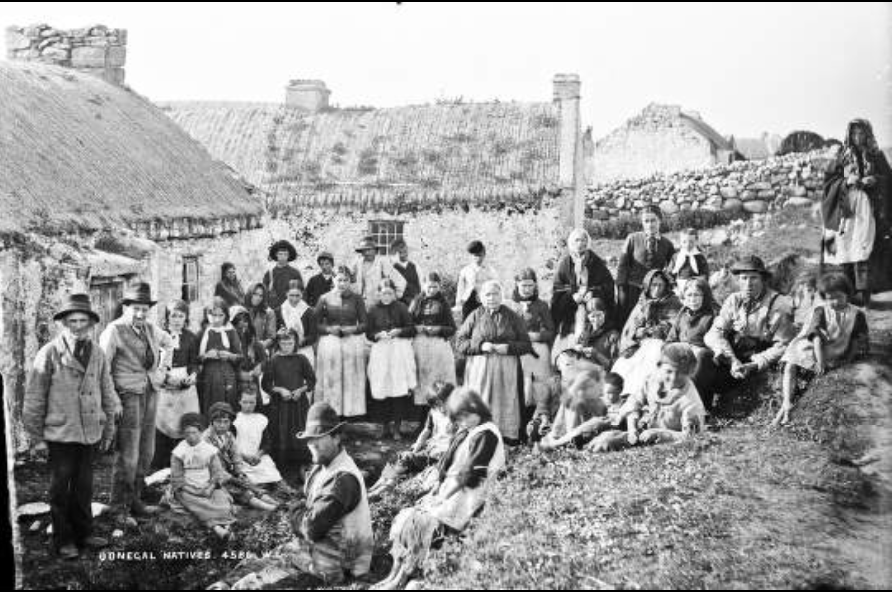

Ruins are a favored haunt of tourists, but the stories behind them are almost always terrible. An image of thatched cottage, complete with cows is quaintly pleasing. The picture entitled “Donegal Natives” taken by French is too: just look at the cottages, with their neat thatch, and the stone wall behind them. If you look long enough, though, your eyes might refocus on the chain of taut hands of the “natives” whose controlled anxiety emanates from this picture. Who looked at this picture? Did they see ruins?

Time does not heal all wounds, no matter how much of it has elapsed. Calling the famine “hard” shows that LookHuman, for all its edgy politically-themed “expressiveness” has no stomach for understanding anything, not feminism and certainly not famines. (Don’t buy your political slogans off the damn rack, people. Make your own tee shirt.) I wanted to know the story behind the tee-shirt, but unsurprisingly neither LookHuman, nor its parent company Print Syndicate, would answer requests for an interview from me, preferring to cower behind their hastily offered (we’re so sorry! we didn’t meant offend!) apologies.

A couple of days after mulling all this over, I ran into a friend on the street. I told him about the tee-shirt. We agreed that we missed the days when St. Patrick’s Day cards were just corny.

“What’s wrong with wishing people good health? Or good fortune?” he asked. “What’s wrong with wishing people luck?”

I agreed. But it’s funny: luck makes me feel wary. My family was lucky. But for every lucky family, there were thousands that were not. I know something about the famine and what it did to people, their families, their communities, customs, memories, their days and nights, the music they made, the love in their hearts, their gossips and quarrels and human needs, and their terrible fear, and bewildering grief. What kind of luck is that? I wonder whenever the subject of the famine comes up.

I never heard the famine called An Gorta Mor until I took a beginning Irish language class at New College. We learned it from Mrs. O’Hara, our Dublin-born múinteoir. The first sentence I ever said in Irish in her class was something I’ve said — along with billions of other human beings — so many times in my life, that I figured it would be a sentence I’d actually use.

Tá ocras orm, I said. I am hungry.

Reposted March 7, 2021