Cherry Lake is the name of a private residential community in Newport Beach. The lake that gives the place its name sits roughly 26 feet above sea level on the northern bluffs of the Upper Newport Bay. Its depth is 17 to 19 feet. It is long, rather than wide, and lozenge-shaped. A water-gate prevents debris from being swept into it from a depressed area that runs from the intersection of Santa Isabel Avenue and Redlands Street. There is a concrete dam on the southern edge that impounds the water with two six-foot pipes inside a catch basin. When it rains fiercely, the impounded water overflows into the pipes that run underneath Irvine Avenue at 23rd Street and through the Santa Isabella Flood channel that drains into the Upper Newport Bay.

Twenty houses ring the lake and many of them have docks. “I’ve seen those docks underwater,” Rodney Medler told me. I’d left a note on his door—can I see the lake? —and he’d called and invited me over for a look. Medler, a retired property manager with the rakish good looks of the actor Sam Elliott, lives on 23rd Street. His backyard faces the lake, and he also has a camera trained on it, so that even when he isn’t outside, he can see it, the better to catch lake-crashers (they’ve had some). Cherry Lake has lily pads. When they die off in the fall, the tuberous roots, which are a ghastly greenish-white, float near the surface of the water, looking like the arms of a monster: the Cherry Lake kraken, perhaps. There’s a slide in the middle. People swim in the lake. It’s a special place.

Cherry Lake has a distinctly retro feel to it. The name hearkens back to the technicolor gloss of the post-war era in Newport Beach. Back then, the colors were bright, and women wore coral-colored lipstick as they water-skied in the bay or drank cocktails at the Village Inn on Balboa Island with their handsome husbands. In those day, everything was gay, and people lived their lives gaily, according to the local newspapers, the Newport Ensign and the Daily Pilot, who never hesitated to use this adjective to describe the mirthfulness of everyday life in Newport.

There was no water skiing on Cherry Lake, although there was fishing. “There are fish in there— bass, catfish, bluegill,” said Rodney. “We fish. But we just catch and release though. They’re like pets!” A woodpecker flew across the lake just then, in a flash of black and white.

“Look at that!” said Rodney. “We get all kinds of birds here. We got some ospreys last year.”

“They must love the fish!” I said.

“Yeah,” Rodney said. He laughed. “We make it easy for ‘em.” The lake was different, he told me. Not only was the bottom unlined, it was spring-fed.

“There are six springs in the lake,” he told me genially. “When you swim, you can feel the water temperature drop. And that’s how you know.”

I’d heard about the spring: it was the lake’s creation myth. But there was nothing plausible about the lake (coastal lakes are relatively rare in California.) It was obviously man-made. But by who?

It was a joint effort. Lawrence E. Liddle, the property owner, joined forces with realtor Jack W. Mullan in 1956, according to papers filed with the Newport Beach Planning Commission. Together, they built a lake.

Both men took their cues from the recent past. In 1955 the Vogel Company, a realty firm, advertised a “lakefront” home on Cherry Lake, with guaranteed swimming rights. A year later, the Soil Conservation Service of the Department of Agriculture graded the area and installed a desilting basin. How Cherry Lake fared during this rough treatment is unknown. But community memory is tenacious, and the recollection of what the site had been probably encouraged Liddle and Mullan.

Liddle, born in British Columbia, kick-started the development of Cherry Lake, appearing as the principle of “Lake & Bay Park, Inc.”. He drops out of the historic record as represented by city filings and newspaper mentions after a time. Mullan, however, stayed in the news until his death in 2004.

Mullan, an adventurous man, was a big-time developer in Newport Beach. As the vice president of the California Real Estate Association in Orange County, he designed neighborhoods out of the raw materials of the Southern California landscape. His large-scale vision was acquired during the war after enlisting in the Air Force. He flew P-38’s, the workhorse fighter aircraft that could bomb landscapes or document them. A renowned photo reconnaissance pilot, Mullan was trained to do the latter, and continued to fly them after he and his wife moved to Germany after the war. Mullan managed the operations of the Aero Exploration Company, based in Tulsa, Oklahoma a firm that specialized in aerial photography. The company had an outpost in Frankfurt, then at a low point in its long history, the cityscape having been almost entirely destroyed from 1939 to 1945 in nine separate bombing sorties.

The view from the skies above war-scarred world stayed with Mullan, who found civilian uses for his Air Force training in post-war Southern California. Mullan “pioneered the use of aerial surveys in subdivisions” according to his brief biography on the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. He moved several times before settling in Newport Beach, and once there, began shaping the landscape of semi-rural Orange County.

Mullan didn’t just develop housing tracts, he provided “estates”, with an emphasis on exclusivity, and all the trappings thereof. Golf courses, clubhouses, private roads and lakes were popular design features of the exurbs, built for those in white flight from diversifying city centers. Mullan took all this to its fullest expression, and masterminded Orange County’s most iconic mid-century housing developments, the “Carriage Estates” in Mesa Verde, for example, which were located on the bluffs above the Santa Ana River.

His most enduring legacy is his credit as the co-designer of a new kind of housing development, called a “condominium”. He oversaw the design of the first legal condo development in California called Vista Bahia, appropriately: they (still) overlook the top of the Upper Newport Bay, at University Drive and Irvine Avenue. I marveled at the grounds of Bahia Vista as a child, walking to swimming lessons at the YMCA. The grounds were impeccable with coarse St. Augustine grass and sculptural hedges of Natal plum (Carissa macrocarpa).

Bahia Vista embodied Orange County’s two great loves, an expansive view and privacy. Mullan built it in anticipation of the coming population surge, which involved more people demanding more of everything — housing, parking, and recreation — except density.

He had some defeats. In 1965, the year I was born, Mullan headed the Newport Dunes Hotel Corporation, which intended to develop the Newport Dunes into a Spanish-themed 244-room hotel and restaurant complex, covering 6.4 acres, and facing “the quiet waters” of the lower bay. A fifty-year sublease was planned between Mullan and the county, but the plan was scuttled in 1967 due to bureaucratic hesitance to commit to the costs of construction. The complex was never built.

But Mullan still built plenty, some of it above the Upper Newport Bay. Within a decade, the bluffs between Mesa Drive and East 16th Street were transformed from small farms divided by eucalyptus windbreaks and dotted with ramshackle buildings into family homes plotted on streets whose names memorialized the cities of old Europe: Grenoble, Marseilles and Seville.

In the mid-fifties, Mullan founded a realty firm and opened an office on the peninsula at 434 32nd Street in Newport Beach, close to Via Lido and just around the corner from my grandfather’s office, the Weist-Creely company, then selling parcels of augmented mudflat on Lido Isle for under one hundred thousand dollars. They were joined by P.A. Palmer, R.C. Greer and others, all of whom were jockeying to sell the undeveloped and sometimes barely terrestrial land of Newport Beach.

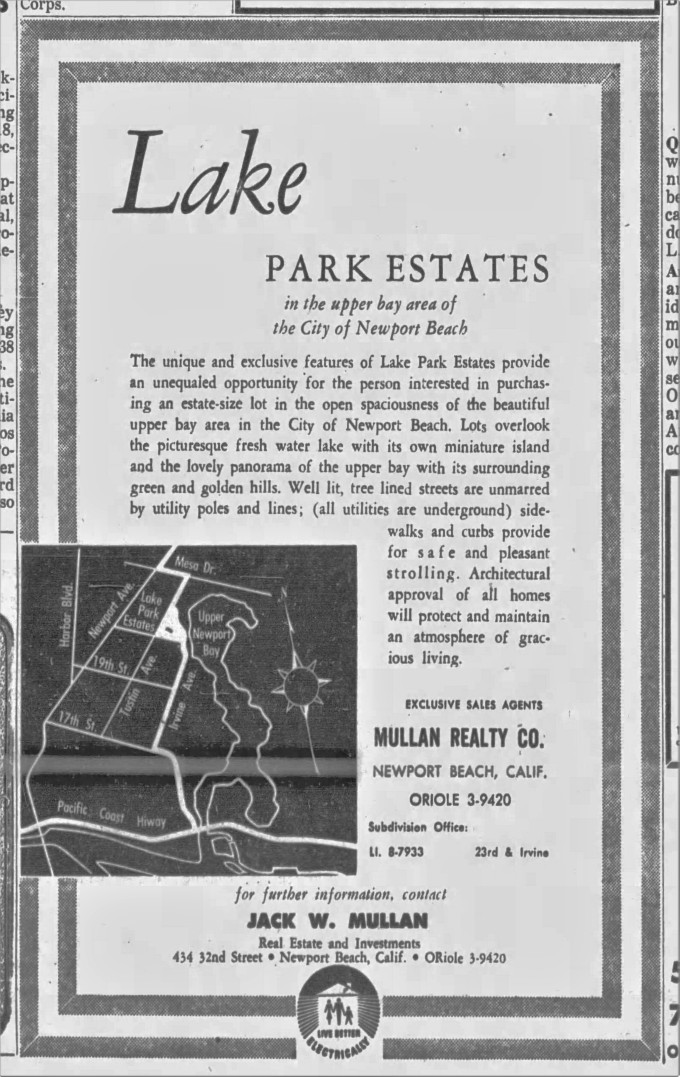

In 1958, after he was granted a permit by the city of Newport Beach to post subdivision signs, Mullan hung two advertisements outside a temporary sales office near the old ravine at 23rd Street and Irvine Avenue, and ran an ad in the Los Angeles Times, alerting the public to a new development with natural allure. “Lots overlook the picturesque freshwater lake,” the ads boasted, mentioning that all utilities were undergrounded, and all architectural designs subject to approval, in order to maintain the harmoniousness of estate life. (There was no mention of the lake’s decidedly un-glamorous stint a year or two earlier as a desilting basin). He and Liddle dubbed the development the “Lake Park Estates.”

The “freshwater lake” was, of course, Cherry Lake, a name not in keeping with the nature of the place. There are no lakes called “kirsch see” in Germany, but there are a few Cherry Lakes in Canada, where Liddle was born. Arranging the site must have been a monumental effort: Mullan, Liddle and their engineers had their work cut out for them. Cherry Lake, and the houses arranged around it, sit on top of what once was a 25-to 40-foot ravine.

After talking to Rodney, I developed an obsession with the mythic spring of Cherry Lake and went looking for proof of its existence. The Sherman Library, which is housed inside an adobe house on Dahlia Street in Corona Del Mar, specializes in the history of the Pacific Southwest, and Newport Beach. I sent them an email, asking hesitantly if they knew anything about it. Jill Thrasher, the head librarian, called me back almost immediately.

“What exactly are you looking for?” she asked.

I didn’t know. “Anything?” I said, feeling dumb (water? a hole in the ground?). I explained that I wanted to see the bluffs of the Upper Back Bay as they were in the early 19th-century, before they were developed.

“Creely,” she said. “That name sounds familiar. Are you related to Bunster Creely?” I told her I was. (The library holds some of my grandfather’s personal library.) She said she’d call me back, and I hung up with low expectations. I didn’t expect much. I’d hadn’t given her much to work with. She called back a day later, her librarian’s natural calm slightly ruffled.

“I think I may have found something you’ll really be interested in,” she said. I shuffled into the library that day feeling foolish—what did I want with that old lake, anyway?—and sat down. Jill had USGS coastal survey maps, or “T-sheets”, as big as posters, spread over the library’s long tables. She tapped one with her finger. “Here’s Cherry Lake,” she said.

The United States Geological Survey, which formed in 1879 to inventory the mineral and hydrological resources of the United States, did all historians (credentialed or not) a big favor by mapping the coast of California. The maps from 1927, 1935, 1942 and 1949 all showed, in spidery lines, a sharply incised ravine thrusting like an accusatory finger out of the Upper Newport Bay, and into Costa Mesa, to what was now Orange and Monte Vista Streets.

In 1927, ’35, and ’42, the area was shown as a marshland. Dotted and dashed lines were interspersed with tufted clumps of grass, symbols that looked exactly like the natural feature they were documenting.

In 1949, after the USGS started using color, a thin blue line appeared for the first time, running down the middle of the ravine. “That’s the symbol for a stream,” Jill said. The past swam before my eyes.

In 1949, my hometown was still being assembled. Irvine, and Tustin Avenue, Santa Ana and Orange Streets were paved. Irvine had yet to cross the ravine and stopped at 23rd Street. Orange Coast College was platted and partially built. The bay had been labeled too. “The Narrows,” a poetic name reminiscent of Ursula Le Guin’s minutely detailed map of Earthsea, was an area directly downstream from the old creek.

Cherry Lake, it turns out, was much more than just a spring. It was mostly a creek that ran through a deep ravine, fed by the artesian belt that Newport Heights was known for. If there were springs, they likely watered the creek south and west of Santa Ana Avenue. There was still more to know: the 1935 T-sheet shows a wetland complex complete with a good-sized pond nestled into what is now the intersection of Bear and Bristol Streets in my home suburb of Mesa Del Mar. (It was still there in 1942.) Looking at the place in the terrain view on Google reveals the remnants of an old bluff curving around the lake between Private Road and Santa Isabella. Today, as you cross Irvine Avenue you are traveling above a ravine that once cracked this area in two.

The earliest appearance of the stream appears on an 1858 U.S. Survey plat map of James Irvine’s property. The northwestern bluffs of the mesa are indicated just under the boundary line with the notation “rolling land.” Another line with another tiny notation “stream of alkali water” appears to the north, cross-hatching the boundary line. But there are no symbols for a spring on any of the historic maps.

This mattered to me, because it mattered greatly to Cherry Lake residents, who, undeterred by the improbability of a spring-fed lake, have always insisted that their lake is spring-fed. But if the old maps didn’t provide proof, community memory did. In 1992, Mullan told Joanne Lombardo of the Newport Beach Ad Hoc Historic Preservation Committee that Cherry Lake was the original well site for Newport and moreover gave the place yet another name: Indian Wells/Springs, which is how the area is identified in the official inventory. Naturally, I called the city.

“Springs? In that area? I’ve never heard that,” said Bob Stein, a civil engineer and hydrologist for the city. “We have seeps around there. But Cherry Lake is probably fed by normal urban slobber.” He meant runoff.

“It does have a relationship with the Upper Newport Bay. Have you seen the Santa Isabel Flood Channel? It’s kind of a pit,” he asked ruefully. “I’d love to do some restoration around there.” He was curious to know more. “Tell me what you find out!” he said.

“According to the map we have, there’s no outlet,” said Linda Candelaria from O.C. Flood control. “It’s a private lake. We don’t monitor it but we’re all kind of curious now. No one has heard of it. You’ve really piqued our interest.”

“Cherry Lake? A spring? We have no idea,” said the woman who sat behind the desk at the Peter and Mary Muth Interpretive Center in Upper Newport Bay. She looked puzzled. “I’ve never even heard of the lake.” A Parks and Recreation staffer, strolled over, regal in her khaki uniform, and said, “I wonder if that’s where the fish came from.”

“What fish?” I asked.

“We found a bunch of dying fish once, about three years ago. Over there,” she said and waved in the direction of Irvine Avenue. “They were just lying there. I wonder if they came from the lake.”

Carla Navarro, from the California Department of Fish and Game said in an email to me, “Cherry Lake is private, self-contained, and does not drain into the estuary.” She added, almost as an afterthought, “I’d be interested in anything you dig up. The lake has been a small mystery to me.”

Bob DeRuff, a former Engineer with the Irvine company, provided actual proof. He remembered the spring clearly because he touched the “natural, fresh water” himself.

“That’s a freshwater marsh,” he told me over the phone. “I used to have a copy of a 1875 hydrographic map. It showed the location of springs around the bay, which included that area. I got it from the Irvine Company—had it in a closet, in the back. One year, I moved and I didn’t take it,” he said sadly. “In high school (he went to Newport Harbor High), I remember a place along the road there, where Irvine is now, up around the lake. I remember getting out of the car with a friend. The land was wet. It was almost like a pasture, but there was a rock outcropping and there was water running out of the ground, over the rock. It must have been artesian enough that something was forcing it out. It was just running out.”

“The whole area was a gully,” he said. “I had a friend who built a house on Irvine Avenue, who had to fill the ground with pea gravel ‘cause the water ran so consistently. He needed it to percolate. You know, until the eighties, Irvine Avenue would come apart on a yearly basis. There was so much water seeping in from underneath. That whole area was wet. You can still see it in the area across Irvine Avenue.” He was talking about the flood channel, known colloquially as the 23rd Street creek.

Other people had memories, too. “That place? Oh, honey. We called it the run-off. It was terrible,” Francis Gowen Kennedy Moran told me. Fran—our childhood name for her —grew up in a house on the corner of 20th Street and Tustin Avenue, which ends above the artificial shores of Cherry Lake. She remembered it all.

“Honey, it was a marsh. It was a mess — just a mucky swamp. Full of mosquitoes. They didn’t know what to do with it. People were always getting into car accidents there.”

I could see that. Tustin Avenue is flat until it intersects 23rd Street. Then the edge of the old bluff gently descends into the basin holding Cherry Lake. Fran continued with her story. “In those days, Tustin dead-ended into the run-off, and there were no stop signs on Tustin, so people would fly down the street in their car and launch themselves into the swamp. And then my dad, who was a doctor, would be called in to patch ‘em up.”

I thought about those heedless people, gaily motoring down Tustin Avenue in the daytime, or through the velvety blue August nights. Did the sulfurous odor of the swamp fill the air? Did croaking frogs and whining mosquitoes provide a soundtrack on hot summer nights? Crashing your car into a swamp and riding your horse over the bluffs to the edge of the cliffs of Corona Del Mar, as my aunt Cerini once did: these were things people could do back then, in non-developed Newport Beach, a place of crashing surf and glittering starlit nights.

Fran’s voice snapped me out of my reverie. “Now listen to me, Betsy. That’s not a lake. It’s a swamp. They turned it into a lake. But it isn’t real,” she said. “You’ve made me really curious. Tell me what you find out, okay?”

The last person I called was Larry Honeybourne, with the county’s Environmental Health Water Quality Section (he has since retired). Honeybourne had a measured, precise way of speaking that busy people who dole out technical information to the public often have.

“Why do people think Cherry Lake is spring-fed?” I asked.

“Well,” Honeybourne said. “It isn’t impossible. There are artesian situations in Orange County. Fountain Valley is called Fountain Valley because of artesian wells. Orange County is an alluvial basin. It’s great for storing groundwater. So there could be springs, if we weren’t taking out more than we put in.”

But they are. Orange County’s water table is overdrawn and has dropped below sea level. The ocean, sensing an opening, has rushed in to fill the gap. At the moment, much of the water filling the subterranean cracks of the Newport Mesa is coming from the sea. The spring that Bob DeRuff knew in his youth may have dried up long ago.

“The ocean is at your front door,” said Honeybourne. “That’s what we tell everybody.”

Fine, I thought, but what about the damn spring? No one answering the phone with polite and perplexed voices at various agencies seemed to know anything. I called my sister Emily, a field scientist who lives in Alaska, to report my findings and the mysteries that remained. Spring or no spring? And why doesn’t anyone know?

“Betsy, “said Emily, exasperatedly. “Government agencies won’t know about a spring.” She was right. They aren’t in the business of history, but resource management.

Resource management, though, does create archival documents, and it is in one of these that the mythic spring of Cherry Lake officially appears. In 1952, an engineering firm with the snappy name of the “Knappen-Tippetts-Abbetts Engineering Company” prepared an environmental report for the Irvine Company on the suitability of their land for urban development.

Knappen-Tippetts-Abbetts concurred with the Irvine Company’s opinion that development was the fate of the area, and noted on page 22 that the “active spring” at the “foot of 23rd Street,” which had been marked on charts 75 years ago, might play a part in some suburb’s future. “Around this spring, a park with lawns and interesting planting,” could be of value, averred the report’s author, due to the availability of “natural fresh water.”

“Well there you go,” said Emily briskly when I reported my finding to her. “Fran is right. It isn’t a lake. Cherry Lake—who came up with that name by the way? It’s silly— is an accident.”

Accidents aren’t as well planned, I thought. The place was just devoid of a past. Ah, the developers, I thought. Those mid-century men, consulting maps, and compasses, grading hills, filling land and damming water sources as they built for the future. They knew what had been there. They had proof. Caught between the past and the future, were they able to forget the habitats they had paved over? Did they remember the scent of brine, or the appearance of an enigmatic petroglyph, or the biblical sight of a spring gushing out of a rock? Maybe. But their memories had died with them, and anyway, they probably didn’t talk too much about it.

“What did Cherry Lake look like?” I asked Emily.

She sighed and said, “Want to go for an imaginary walk?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Close your eyes,” she said.

She and I started walking on the mesa southeast toward the ravine. “So, this is what we’d see,” her voice said, out of the telephone clutched to my shoulder. “First thing, we’d see a bunch of shrubs. Remember- we’re on top of the bluff. So think about what grows there. Sage, for one thing.” She meant the clumps of Artemisia californica, the ubiquitous silvery green sage that forms the top note of the scent of the California coastal chaparral.

“Try to see coastal oak,” Emily urged. I saw old man oak, the gnarled trees that look more like a shrub, with fang-toothed leaves. “The color of the landscape changes,” said Emily, “as we get closer to the ravine. Can you see that?” I could. The soft grey-green of the artemisia sharpened into yellow- and olive-green as the tops of sycamores and willows appeared. The smell changed, too, from the lemony scent of the artemisia to the dank heavy odor of water. There was a faint suggestion of sulfur.

We stood on top of the ravine and looked down. Below us, fringed by red-rooted willows was a pool of dark water. A pond. Not a lake.

“If we went down there, we’d step in mud,” said Emily. “And then suddenly there’d be water, open water, like a little pond.”

“It was beautiful then, right?” I asked.

“Yeah,” she said. “We would have loved it. I have to go to sleep, babe. You have a better idea of what it looked like?”

“Yes,” I said. We hung up.

There’s no mystery to the origins of Cherry Lake: it’s private, not mysterious, a post-war folly that started in the skies of the Pacific Theater and came down to earth when Lawrence Liddle and Jack Mullan stood at the top of a deep ravine and beheld murky water pooled in the bottom. If there’s a mystery, it’s this: what do you see when you look at a landscape, and why? I guess it depends on where you’ve been. Mullan, who had beheld the ravages of war, saw something comprehensible, an opportunity for serene, untroubled beauty.

Cherry Lake is both real and unreal, an artifact twice over. It was a spring-fed stream dividing an arid plain in two, then a desilting basin and then, finally, a suburban fantasy. No one can transport an entire world to another place, Avengers-style, but with the means and the drive, you might be able to re-create a spatial simulacrum of place, scaled down for the suburbia, and far more secure. The earth as seen from the cockpit of a P-38 must seem so malleable. It is easy, as Mullan knew too well, for places to change (to vanish), and for landscapes to be exchanged for another.

Finished in San Francisco on April 18th 2020, 31 days into shelter in place, and eight years after I started researching Cherry Lake.

This is dedicated to my brother James W. Creely with love. Many thanks to the Jill Thrasher at the Sherman Library, Bob DeRuff, Julie Goldsworth of the Irvine Historical Society, Andrew Page of the Newport Beach Public Library, the fabulous Fran Moran, and the staff of the UCI Special Collections and Archives.

I over-researched this essay. If you want to see some of the cool papers and maps I found, head over to this repository and check ’em out.