“Hello! Hello! Is this Mr. Seidenberg? Is this Mr. Davis? Is this Mr. McAlfrey? This is McCarty at the Cliff House.” 1

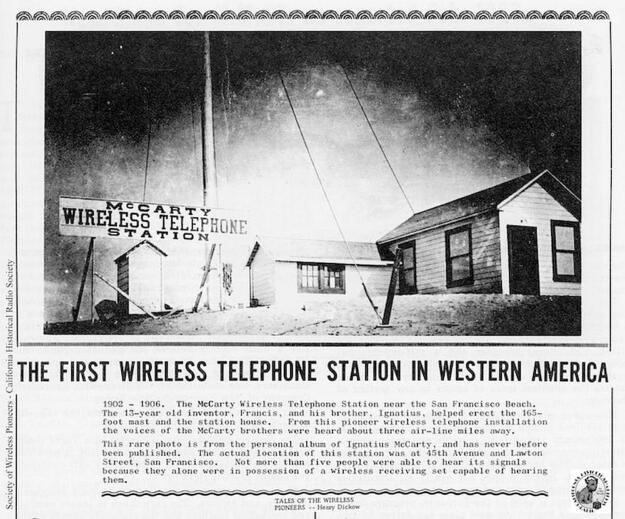

My cousin Francis Joseph McCarty occupies an interesting place in the history of emerging mass communications technology in the early 20th century. Francis is credited with manufacturing and demonstrating the first wireless telephone in San Francisco, and founding the first wireless telephone company on the west coast, making him an unlikely forerunner of today’s tech bros and their famously disruptive culture.

He was only able to invent one thing before his death at the age of 17 in 1906, but that one thing — a patented wireless telephone—had an immediate impact. The bulky device spawned two more wireless companies, both short-lived, a silent movie, now lost, and a starting point, not the basis, for the founding of the Federal Telegraph Company in Palo Alto by Cyril Elwell, who launched a new generation of wireless voice transmission.

I was in my thirties when I met my cousin posthumously because of a writer’s inadvertent biographical error. In the AWA Review article “Wireless Comes of Age on the West Coast”, writer and California Historical Radio Society member Bart Lee mistakenly identified Daniel “Whitehat” McCarty as Francis’s father. I’m grateful to Lee for this excellent article, and happy about the error. Researching anyone named McCarty in San Francisco is tough work, however, Whitehat acts as a sort of indicator species for our family—when his name appears in a newspaper article, you know you’ve found the right McCarty. Too, there’s been on-going confusion about who did what wirelessly, with more than one writer accepting the origin story put forth by Francis’s older brothers, Ignatius and John, who, riding hard on Francis’s coat tails, identified themselves as the founding inventors of the telephone, as each man tried, and failed, to continue their brother’s work.

Francis probably wouldn’t have been surprised by the idea that his Whitehat was his father, whose zany notoriety attached itself to anyone in his orbit. His connections with city hall and San Francisco’s high rollers made it easy for Francis to court media attention for his device, then, as now, an important strategy for attracting investors. But Whitehat was not Francis’s father.

That honor belongs to John Henry McCarty, Whitehat’s jealous younger brother, who lived a pale life in his brother’s exuberant shadow and in the aftermath of his son’s invention. Francis’s paternity was uncertain, not because he didn’t know who his father was, but because as far as we can know, his father didn’t appear to care that he had a son. John began to leave his family sometime in 1904, depriving his wife and four young children, including Francis, of a source of income, and a crucial skill: the ability to handle a horse.

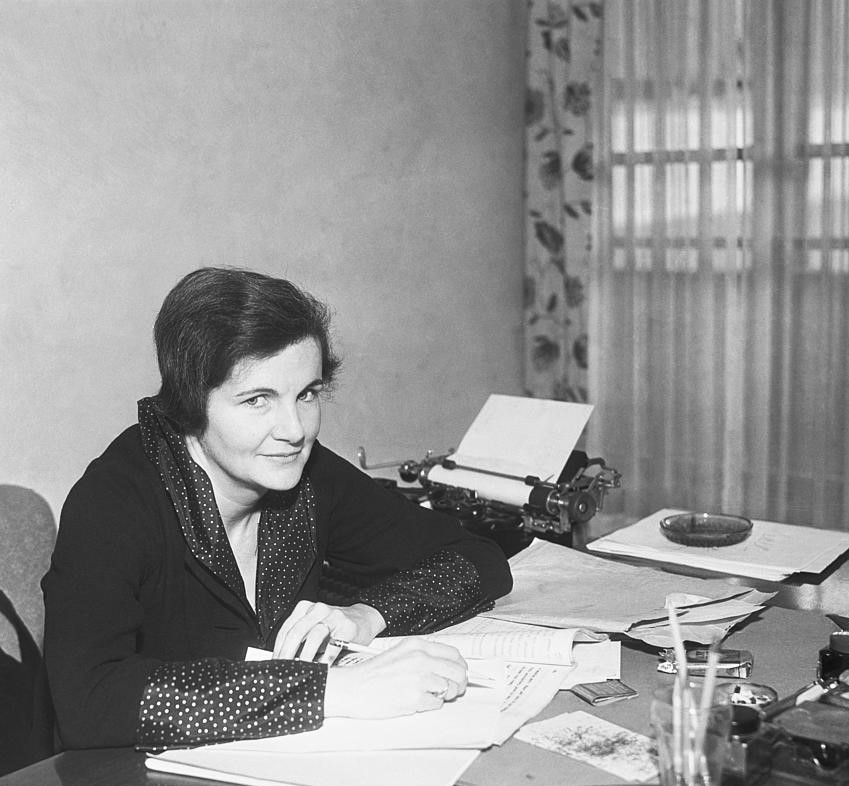

John had been absent for years before he actually left, according to Mary Eunice McCarty, Francis’s younger sister, a screenwriter in Hollywood, and the sole source of information about the interior life of the McCarty family. Mary was a redoubtable woman, once called the “Joan of Arc for the Democratic party” for her impassioned campaign on behalf of Al Smith, the Democratic candidate in the 1928 Presidential election. She wrote at least 13 screenplays, and two books, one of which was a biography entitled “Meet Kitty”, about her high-spirited, resilient mother, Catherine “Kitty” Lynch McCarty.

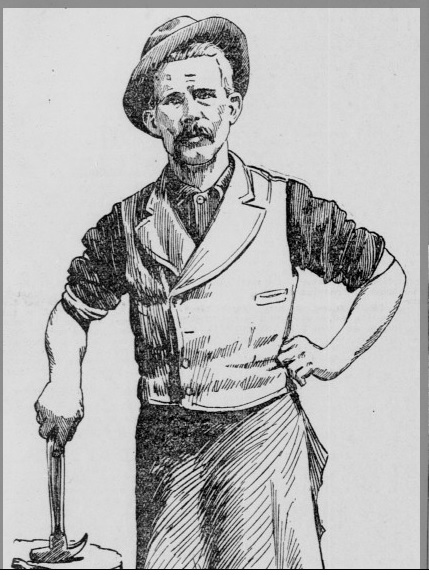

Kitty Lynch arrived in San Francisco in 1867 as a nine-year old with her Irish immigrant parents, and married John, a blacksmith and farrier in 1878. Two years later, the McCarty family was living at 3 Rausch Street in the South of Market. John and his brother James, who lived with the family, were both horseshoers, then the official family business. John, who once pointed a gun at a crowd of angry men from the horseshoer’s union in front of his forge on Golden Gate Avenue, was not a nice man or a good father, according to Mary.

“It is impossible to be temperate in describing John Henry McCarthy,” wrote Mary. “There are not enough words in the English language to give him the full measure of condemnation.”

The exact source of John’s discontent is lost to time. John, who left Bedford, Massachusetts after 1870, and followed his siblings west, carried an enormous chip on his shoulder, and liked to throw it at other people, especially his tiny wife, who weighed less than 100 pounds and survived 14 pregnancies. Eight of her children grew to adulthood.

Mary thought that John’s problem was easily explained: he was an envious, status-conscious man who was more defined by his relationship to his brother Whitehat — and later his dead son—than he was for anything he did.

“Practically every book written about San Francisco devotes pages to Whitehat,” she wrote. “His brother is not even mentioned.”

John and Whitehat did have a lot in common, namely bad habits that ballooned into big problems. They gambled on everything: horses, mostly, and once the outcome of the 1888 Presidential election. They made extravagant “gold-flinging” gestures of bonhomie that they could not really afford in establishments like the Palace Hotel, and the Poodle Dog. Neither Whitehat or John seemed to be concerned with the future—gamblers tend to live in the moment— or could have predicted it as clearly as Francis did, who often spoke of a time when voices would be transmitted by tiny devices.

But at least one of the brothers was smart enough to see that the McCarty Wireless Telephone Co. could be a springboard to wealth and fame. Whitehat was an early investor in his nephew’s start-up. John seems only to have become interested in it after his son’s death.

Hey! Here comes John Henry!

John did try to make his mark. “My father…accomplished something that Whitehat never attempted,” wrote Mary. “He was elected to the California State Legislature.” In 1889, John H. McCarty served as the California State Assemblyman from San Francisco’s 39th Assembly district in the 28th session. This should have provided him some sort of distinction, and yet, as Mary remarks caustically, “…the spotlight eluded him. No one ever said, Hey! Here comes John Henry!” John’s single term in the State Legislature failed to make any lasting difference to his life, perhaps making his already large chip even bigger.

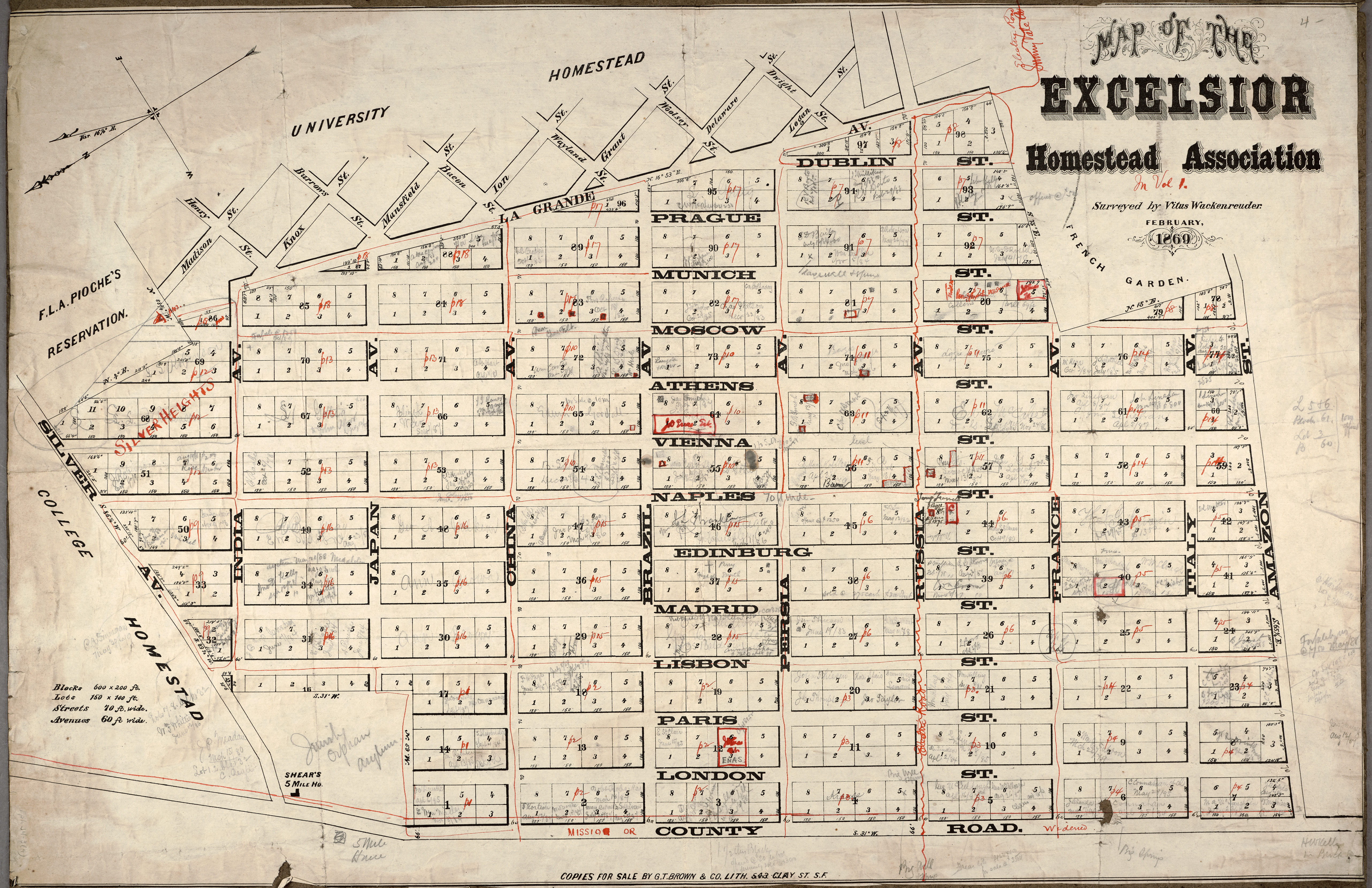

In 1888-89, San Francisco’s 39th Assembly district encompassed the 8th and 11th wards in the Tenderloin, Civic Center, and South of Market neighborhoods. These crowded districts were home to laborers, sometimes skilled, and sometimes not, often from immigrant Irish backgrounds. John first owned a horseshoeing business with his brother James, and later with another Irish-American blacksmith, Francis O’Neill in the Civic Center, the perfect locale to meet and mingle with ward bosses and city supervisors.

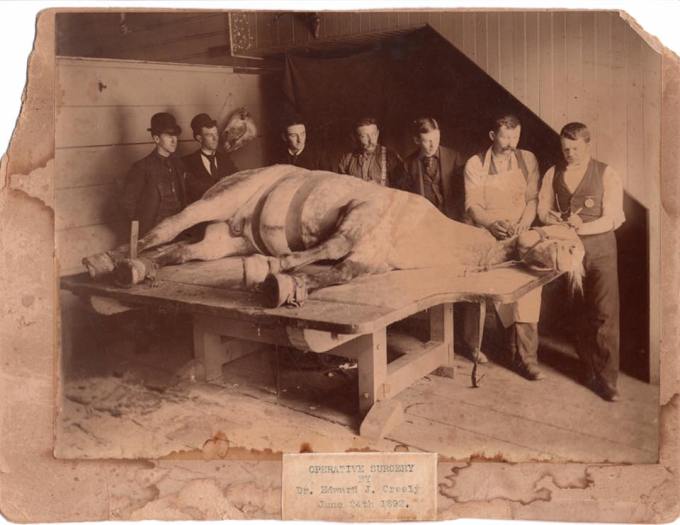

Like his nephew Edward Creely, John took his political cues from where he was at: a dense, socially intertwined neighborhood where the electorate were met at the polling place on election day by a prepared ballot, or ticket, and a ballot box guarded by “…the watchful eye of party workers”.

Which party they voted for was a question. In the fall of 1888, there were plenty. This was the era of the independent party in San Francisco. In the excellent book on San Francisco politics entitled “San Francisco 1865-1932: Politics, Power and Urban Development”, historians William Issel and Robert Cherny describe the electoral system as “unregulated” and vulnerable —or responsive depending on one’s perspective— to the ambitions of electoral entrepreneurs who, seeking a path to power, founded new political parties if they commanded a sizable constituency, could pay for ballots, and deliver votes.

The ephemeral nature of political clubs in San Francisco at this time is head-spinning and hard to document 135 years later, but there was one consistent theme in the fall of 1888: the exclusion of the Chinese and the passage of the Scott Act, which expanded the powers of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 by barring resident Chinese laborers who had traveled back to China, from returning to the United States, even if they had certificates allowing them to return.

The Scott Act was signed by President Grover Cleveland in October 1888, just eleven years after San Francisco’s Chinese community was subjected to the terrifying Sandlot riots in 1877. Bellicose speeches delivered by Charles C. O’Donnell, and later Denis Kearney, whipped up mobs of white laborers who swept through the city’s east side, destroying Chinese-owned businesses and killing four Chinese men. The riots coalesced into the Workingmen’s Party of California, led by Kearny, which left an indelible stamp on city politics, and cadres of men eager to continue the business of the WPC, long after its end by 1881. In light of John H. McCarty’s brief legislative career, one wonders where he was during the Sandlot riots. It’s a fair question.

It was this tradition of immigrant nativism that swept the “horseshoer”, as McCarty was described, into office as the candidate from the newly formed “Foreign American Independent Party”. John was nominated on October 11th, 1888 at the Thirty-ninth Assembly District Democratic Convention.

Patrick A. Dolan headed the new party, but the party actually had two daddies, the other being the former Sandlot orator, Charles C. O’Donnell, a physician, and former head of the Sarsfield Rifles, a National Guard company. “Dr.” O’Donnell, as he was mockingly known (historian and author Beth Wingarner delves into his sideline occupation as an abortionist here), frequently appeared on the sandlots to shout that the Chinese must go. O’Donnell himself isn’t mentioned in the lists of the officer’s names of the Foreign American Independent Party, but it bore the imprint of his sinophobia so firmly that the candidates were called “O’Donnellites” by the Daily Alta.

This was John’s ticket into government: populist bigotry and nativist rancor. How horribly ironic that its first meeting was held in the huge Irish American hall of San Francisco2.

Cleveland’s Anti-Chinese wall

On November 3, 1888, three days before the election, the democratic clubs in San Francisco organized a parade to show support for the presidential incumbent, Grover Cleveland, tariff reform and the Scott Act. The massive march was designed to rouse the voters and strike terror into the hearts of the city’s Chinese residents, who were treated to a display of 15-20,000 white men walking in military formation dressed as Zouaves, Vaqueros and “Iroquois”, complete with guns, torches, and incendiary devices. The march started from Montgomery and Kearny Streets and proceeded down Market to Franklin.

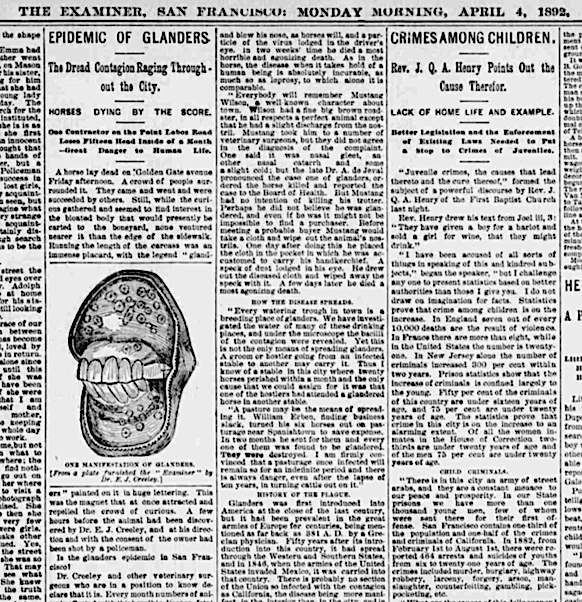

The Daily Examiner reported on the spectacle with pleasure. “The city of 400,00 white people got its 6 o’clock dinner over as quickly as possible, sent its servants about their business, locked up its house and started for the streets”. Spectators lined Market to watch the procession of Democratic clubs, and their assembly candidates make their way down Market Street.

McCarty’s future colleagues Henry C. Dibble, Thomas Seary and Thomas Brannan, all from neighboring districts, walked in the parade. John joined the other members of his trade, the Ironworkers of the city, on a horse drawn wagon. The boilermakers’ exhibit featured a huge boiler being riveted by workmen, whose brawny muscles stood out in bold relief under the glare of the furnaces. McCarty, the nominee from the 39th district, struck a pose atop the float with eight other men, “lustily” pounding out a horseshoe on an anvil.

There were other floats, too. One, captioned by the Examiner as “Cleveland’s Anti-Chinese wall” featured a wall, encased in a wooden box with the words “Harrison’s Idea of Protection” and “Indiana, sure you bet” painted on the side. Two figures were painted on the banner sitting on scaffolding. The digitized images available online have lost some detail, but one of the figures appears to have a queue hanging down their back. Taken in the wider context of its appearance in an anti-Chinese parade, the message seems clear.

The red glare from the torches, and the fiery trails of mortars fired into the air lit the upturned faces of the spectators who were transfixed by the fantasy spectacle of the whites-only march. In an adjoining story, the Examiner stated that their “canvassing corps” had polled over 3,000 people to discover the mood of the voters. “The results of yesterday’s canvass shows that among the working people and those of small capital the Chinese question seems to overshadow all other issues.”

Polls, as we know, can be wrong. The canvassing results may have given Cleveland the edge, but to no avail. Benjamin Harrison won. Cleveland won the popular vote but lost the electoral vote. It was a bad day for the Dems at the federal level; however at the city level, things went well for John and his Foreign American Independent party confreres. The party won 15 out of 20 assembly seats in San Francisco. Out of 2,715 registered voters, John won 1,249 votes against his republican opponent J.H. Goldman, who secured 1,141 from registered voters, all of whom began voting “unusually early” (Daily Alta Nov 6, 1888) Of the 19 assemblymen sent from San Francisco to Sacramento for the 28th session, fully half were first-generation Irish Americans.

“We have the Chinese locked out …,” said the Daily Alta, “and we want them to stay locked out.”

The Hibernian Parrot

John was promptly appointed Chairman to the standing committee on Chinese immigration and Emigration. Joining him was Thomas Seary, J.A. Mullaney, Hamilton H. Dobbin, E.C. Tully, M.C. Chapman, C.H. Porter, H.M. Brickwedal, and Philo Hersey. The remit of the Committee was to “take into consideration all propositions relative to the tendencies of Chinese labor upon the political, social, physical and moral conditions and affairs of the State.”

John started off promisingly enough. Dubbed “the learned blacksmith”, he was praised by the Sacramento Daily Union as “…one of the prominent statesmen on the Democrat side of the house. As Chairman of the Committee on Chinese Immigration and Emigration, he strikes terror to the pagan hordes who seek our shores…. Mr. McCarty is a bosom friend to the leading millionaires who frequent the Palace Hotel, and it is understood that he aspires to some of the highest offices within the gift of the people. And well he may, for he is as good as he is beautiful3,” proving the adage that beauty is ever in the eye of the beholder.

On January 25th, 1889, John and other committee members visited San Francisco’s Chinatown, ostensibly to report on the living conditions of the area, but in reality to push for the full enforcement of the Scott Act. In his February 11th address to the Assembly, he wasted no time leveling the Three F’s of nativism at the Chinese: filth, foreignness and fecundity.

“The Chinese are foreign to our living, race and language,” said McCarty “They have little regard for morality, decency or law. They are an ignorant and superstitious race.”4 He concluded his speech with a forceful plea for the Scott Act to be fully enforced, stating that only when the “Oriental invader” was barred from entry would the “sweet voices and joyous laughter” of happy children ring out.

This speech, a fine example of the Irish becoming white (it’s very possible he attained fluency in the language of exclusion, growing up as a child of Irish immigrants on the East Coast) may have been the high point of his legislative career. Other than this report, and two bills, which were just resolutions, he seems to have fallen back to earth. After being described as “beautiful”, the media adulation stopped. A journalist with the Sacramento Bee mocked both his national origins, and his lack of independent thought by dubbing him the “Hibernian Parrot”. McCarty earned a reprimand from speaker Robert Howe after wiping his feet on the top of his desk. “McCarthy is not used to being among gentlemen,” the Sacramento Bee concluded. Later that year, some wag nailed John’s hat to his desk.

Either the fickleness of the party (which seems to have evaporated), or perhaps his personal shortcomings prevented him from gaining the nomination a second time. The 28th session of the California state assembly only met from January to March that year. In late 1889, Charles S. Arms, who went on to become the State Senator from the 23rd district, replaced McCarty in the 39th Assembly district.

For a man so profoundly fond of “the sweet voices” of children, it’s likely he didn’t hear Francis’s voice very often, who was less than a year old when his father invoked the happiness of children as a reason to harrass and exclude the Chinese. After his brief success in electoral politics, John filed for bankruptcy in 1891, and worked as a horseshoer for the next decade.

The Boy who Died

On May 8, 1906, 20 days after the San Francisco earthquake, Francis lost control of his horse on the corner of Fourth and Broadway Street in Oakland, where he had relocated the McCarty Wireless Telephone company. He was thrown headfirst from the cart he was driving, into the concrete curb. He died three days later of pneumonia after sustaining compound fractures in his jaw and broken ribs. His mother was inconsolable. His father’s reaction was more pragmatic. He sold the patent on his son’s invention, and, taking the proceeds with him, finally moved in with his inamorata, a woman named Minnie E. Douglas.

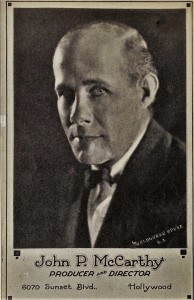

John spent the next several years ducking child support, allegedly with the help of his mistress, and constructing a series of hastily improvised identities. He claimed that he was just a poor chauffeur when Kitty finally hauled him into court for child support in 1907. Kitty, who sought $200.00 a month for herself and her four children, told the judge that with the connivance of Ms. Douglass, that John was hiding at least 50,000 dollars, and probably more, in a dummy corporation called the “National Vulcanizing Rubber Company”5 that included an interest in his late son’s estate valued at $40,000 dollars. John Henry got thrown in jail, but “aided by his own glib tongue and an expensive lawyer”, he never paid a cent in child support. Later, he described himself to the press as the “president” of the “Universal Wireless Telephone Company”, an abortive attempt by McCarty Sr. and his son, John P. McCarty, to cash in on Francis’s invention. By 1914, father and son concluded there was nothing more to wring out of Francis’s invention. Both moved to Los Angeles.

J.P. McCarty stayed in mass communications by becoming a film director in the growing entertainment industry in Hollywood. In 1914, he made a silent movie entitled “The Wireless Voice” starring himself and a wireless apparatus, perhaps of his brother’s design (it’s unclear whether J.P ever built a wireless telephone himself.) His sister Mary and brother Henry A , both screenwriters, enjoyed moderate success. Mary wrote “Theodora Goes Wild”, a comedy starring Irene Dunne, who won an Oscar nomination for Best Actress.

It’s not clear what happened to John in the last decades of his life. Probably not a lot. In 1921, as a 66-year old, he lived with his son J.P., at 7521 Emelita St in North Hollywood. He was alive in 1924, when he was mentioned in his brother James’s obituary. But after that, nothing. No death notice, no loving obituary, at least none that I can find.

It’s hard to write about the son without writing about the father and in Francis’s case this is especially true. Much of what he accomplished was in spite of what he didn’t have: money, a lengthy formal education, and a father who was also a parent.

Retrospectively, John’s absence seems to be the most glaring on the day of his son’s death. It’s unfair to blame John for the road conditions (the culprit was the consequence of a horse sharing the road with cars) but it’s hard to wonder what might have been if he’d been around more. Would Francis have been able to control his horse? They were the family concern: Mary attributes her father’s stint as Leland Stanford’s ranch manager in 1887 to his “expert knowledge of horses”, an expertise shared throughout the McCarty-Creely family. Did John teach his son the art of horsemanship? Or did he mostly slap him away “for his importunate questionings”, as he once admitted to a reporter?

Francis will always be the Boy Who Died. If the details of his life had been reworked into a work of science fiction with the same sad ending – Boy Wonder Projects Voice Through the Air! Boy Wonder Dies! – then surely a work of fan fiction would have emerged, too, one with an alternative ending, in which Francis did not die, but lived long enough perfect his wireless telephone, grow his startup and maybe as a very old man, get a glimpse of the era he knew was coming- a time of tiny phones, small enough to sit in a pocket, and powerful enough to effortlessly transmit voices through space and time. “We have had to fight the hard knocks of disbelief all the time,” he told an Examiner reporter in the fall of 1905. It was a very hard knock that killed him; the disbelief he encountered, including his father’s, he survived. Aside from inventing his wireless telephone, this is perhaps his greatest achievement. Rejection has disabled more than one would-be Great Innovator. Francis died with his sense of purpose intact. That is heroic.

*About the name: it’s spelled McCarty. The Hollywood McCarty’s used the extra “H”, probably because they got tired of correcting everyone. I’m very sorry I never met Mary. She deserves some ink spilled on her behalf. Her book “Meet Kitty” is as much about rejecting her father’s anti-Chinese bullshit, as it is about telling the world about her fabulous mother. Watch “I Hate Women”, a baldly titled B-film that Mary wrote in 1934– it’s got some snappy dialogue in it.

Written with love to Kitty Lynch McCarty, who clapped back at the limits of tolerance when it mattered, and to my boy-genius cousin, Francis.

Thank you to Beth Winegarner, whose book “San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History” is a must-read. And big, big thanks to Bob Rydzewski and the crew at the Bay Area Radio Museum in Alameda. Without their care and attention to the story of the McCarty Wireless Telephone Co. this tiny tale of early San Francisco tech might not be as well known. I am grateful.

- “Talks Through the Air without Wires” San Francisco Chronicle, Sept 3, 1905 ↩︎

- September 21, 1888 (page 6 of 8). (1888, Sep 21). Daily Examiner (1865-1889) Retrieved from https://www.ezproxy.sfpl.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/september-21-1888-page-6-8/docview/2132264028/se-2

↩︎ - Sacramento Daily Union, Volume 61, Number 5, 27 February 1889 ↩︎

- California State Assembly Journals 1889 Session,https://clerk.assembly.ca.gov/historical-information/archive-list/california-state-assembly-journals-1889-session?field_archive_type_value=Journals p. 345

↩︎ - San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, California), September 19, 1908: 14. NewsBank: America’s News – Historical and Current. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.sfpl.org/apps/news/document-view?p=AMNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A142051F45F422A02%40EANX-NB-14DC40A41A695CF8%402418204-14DA452198CDEFC6%4013-14DA452198CDEFC6%40.

↩︎

↩︎

↩︎

↩︎

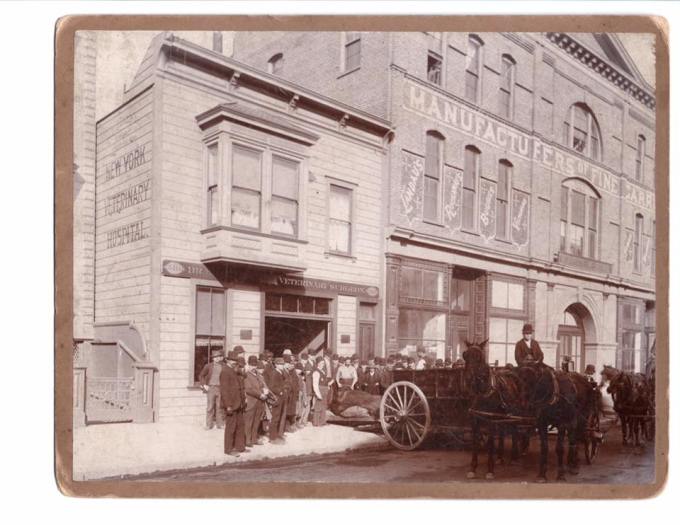

Office of Dr. E.J. Creely, first veterinary hospital in S.F. June or late May, 1906. Golden Gate Ave. (#510), near Polk. Creely is barely visible on the roof of the building. From the California Historical Society, and available at the

Office of Dr. E.J. Creely, first veterinary hospital in S.F. June or late May, 1906. Golden Gate Ave. (#510), near Polk. Creely is barely visible on the roof of the building. From the California Historical Society, and available at the

I was remembering all of the above history today, as I greeted the Irish who were in full

I was remembering all of the above history today, as I greeted the Irish who were in full