“Information on the origin and early development of the secondhand bottle trade is elusive.” Jane Busch, Re-use in the Eighteenth Century Second Time Around: A Look at Bottle Re-use

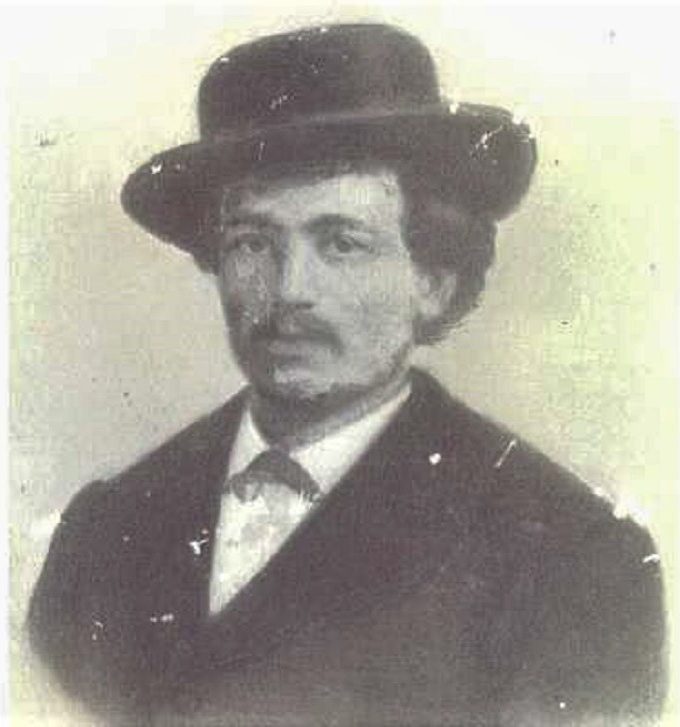

Francisco Cerini, my great-great grandfather, was born in Florence Italy in 1836, and was living in San Francisco by 1858. An adult relative told me that Francisco, or “Frank” as he called himself in America, arrived in California with a bible and a gun, and on the run from Garibaldi, but this is doubtful. Francisco may have flounced out of Italy in a fit of anti-Republican pique, but both items were purchased in San Francisco. He probably bought the gun, a Colt 1851 Navy revolving pistol, first.

There was one object he did arrive with: a pendant with a portrait of himself as a child, wide-eyed, poised and dressed in a manner that looks vaguely orientalist, but is perhaps authentically Florentine. He looks like the son of a prosperous house, one well-off enough to commission a portrait of their young child. Much later, someone had the portrait made into a full-sized painting, which ultimately made its way to my grandparent’s house in Newport Beach, where it hung on the wall behind the sofa.

I think it was from his avidly anti-Communist grandson, Bunster Creely, in whose house the portrait hung, that the dramatic story of Francisco’s escape from Italy originated. But it’s all guesswork. The guy who would know—Francisco—said nothing of the matter, nothing that survived the ages, anyway. He died of the DT’s in 1880 leaving behind a widow, four children and an empty bible, stripped of information and as meaningless as an unused date book.

Francisco must have had fond memories of Florence because he named his daughter, my great-grandmother, after the place. Both she and the name “Cerini” which we have since used as a first name, are the only signifiers of that long-ago home– that and polenta, which my father called “cornmeal mush” when I was a child. My grandfather Bunster called it by its real name and had a habit of saying “po-lenty of polenta,” in a resigned manner when my grandmother served it to him.

Francisco left Italy as young man, maybe 20 or so, leaving behind a family history we know nothing of, only the trivial fact that his surname means “candle” or “match”. Come appiccare un incendio senza cerini? How to start a fire without matches? How do you set your life aflame in a barely constructed city, far away from where you were born?

In those days, San Francisco did nothing but burn. In 1858, the year Francisco first appears in the city directory, seven fires ripped through the Barbary Coast, near Sullivan’s Alley, now called Jason Court, which was where he first lived. Sullivan’s Alley was a short walkway between Jackson and Pacific and a notoriously bad street. It’s easy to romanticize the Barbary Coast now that it’s been tamed by the passage of time and self-guided walking tours. But when Francisco was living there, it was a tense and terrible place where murder, robbery and rape frequently occurred. It was also full of saloons, which might have given him his metaphorical match. Francisco Cerini was a bottle dealer.

I don’t know if Francisco mucked around in refuse heaps, or if he left that for others, but whatever he did, he wasn’t facing too much competition. Only five or six bottle dealers show up in the city directory during his twenty-two year career. Bottle dealing was apparently a niche trade in a sprawling recycling enterprise that mined the city for its rubbish, like the Sierra was mined for gold. In fact, the two are often compared to each other, in recognition of the fact that placer mining, and scavenging have a lot in common. When Francisco found an intact J.H. Cutter whiskey bottle, did he experience a sense of striking it rich? (Was he prone to compulsion?)

Discarded glass bottles were certainly easier to find than gold. In the first decade of the city’s existence, demand for bottles was high, and supply was low. When Francisco arrived in San Francisco, there were roughly 60,500 people in it, and none of them was making glass. It is a demanding medium that needs skilled labor and a large factory equipped with melting pots, furnaces and enough fuel to combine silica, lime and soda ash and coloring ingredients into glass. The resulting bottle had to be sturdy enough to hold whatever you were decanting into it, alcohol mostly, but also camphene, laudanum, linseed oil, vinegar, bitters and later, milk.

It took more than four months for anything to arrive from the east coast in those days, so until glass production kicked into gear in San Francisco, one had to make do with what one could find, or pay someone else to find. Hence the bottle dealer: a man who knew where the bottles were buried, knew how to get them in bulk, and had enough determination to dominate the trade. My great-great grandfather, who was a highly motivated individual, must have walked around Chinatown and the waterfront among the brothels and saloons, looking for bottles, seeing glints of amber and green, and experiencing the same kick of visceral pleasure I feel when I find something of value that has been discarded in the Mission District.

Baker and Cutting, the first glassworks in San Francisco, opened in 1859, a year after Francisco got into the trade. They failed fast and closed in less than a year. A year later, the San Francisco Glass Works opened. “Number of men employed, 10. Capacity, 4,000 pounds per day. An abundance of material for the manufacture is to be found in this State, and a remunerative field is thereby open to the enterprising proprietors of these works.” Francisco and his neighbor, a man named Joseph Zanetti who was also a bottle dealer in Sullivan’s Alley, were among those enterprising men, along with Guiseppe Tomosino who had a bottle depot in Sullivan’s Alley.

Francisco does not appear in the 1860 census or the city directory. He may have been displaced by a fire that broke out in the alley in July, or the neighborhood might have been so insane that census workers avoided it. He re-surfaces in the 1861 directory as an employer, with Guiseppe Tomosino as his sole employee. Both were living at 813 Montgomery. Francisco had since diversified and was also dealing in burlap bags that according to my grandmother’s precise notes were used for vegetables (One of his buddies was a vegetable dealer named Luigi Giannini, whose son Amadeo founded the Bank of Italy, later the Bank of America.) He also dealt in rags, which were valuable to paper mills, like the Pioneer Paper Mill, whose depot was at Davis and California, then as now, was a brisk 15-minute walk from Francisco’s place of business on Montgomery street.

Francisco was a relatively well-off man, and his career as a bottle dealer doesn’t square with my understanding of that. As a child I was told by another adult, dreaming of the lost past, of the Cerini house, which had a carriage stone with a large “C” engraved on it. The house and the stone was located in Oakland’s Central Homestead, on a city block that Francisco also owned. Bottle dealing might have been enough to start some kind of life in the growing city, but was it lucrative enough to allow Francisco to purchase a city block?

The Daily Alta reporting on the scavenging operations at Oregon street below Drumm, allowed as it might be.

“It is not a business to which a man of refined taste and a delicate sense of smell and touch would be expected to take with any degree of satisfaction, but nevertheless it is evidently a paying one,” the Alta reported in 1867, adding that “… many a miner delving wearily in the mud along the foothills of the Sierra, and even more of the more pretentious merchant and stock operators of our city would willingly exchange profits with these rank smelling rakers of refuse…”

Maybe. But turning a profit depended on how intact the bottle was. Francisco may have sold broken glass to the Pacific Glass Works, which used shattered bottles as “flux” in the clay pots used to manufacture glass. They paid one cent for a pound for green and black glass. 100 pounds of broken glass, which works out to about 30 dollars, is both a lot of glass and a lot of effort. But even if Francisco was a sinister “padrone”, a Fagan-type character who used child labor to scavenge for him (which hopefully he wasn’t) broken glass was not a stable foundation for financial security.

Family can be. It’s likely that Francisco met his future wife, Mary Cassandra Conley, because of trash. Mary was the daughter of Martin and Celia Conley, Irish immigrants from County Galway, who came to San Francisco before 1860 from Massachusetts, where Mary was born in 1848. Martin was a junk dealer who lived with his family on the opposite side of town from Francisco at 638 Brannan street between 5th and 6th streets, across from the trainyards and beyond those, the open and garbage-strewn banks of Mission Bay.

I have no idea exactly where Mary, who had enormous blue eyes, met her handsome Italian husband, but narrow streets with no cars make small towns out of growing cities and l’amore trova sempre la strada. In 1862, the two were married. By 1863, they had their first child Giovanni, and shortly after that, Francisco moved his business to a warehouse at 207 Davis and his family to 455 Tehama street near 6th, where his daughter Florence was born in 1868. His in-laws lived less than a mile away, which is maybe why the family lived in the Irish South of Market and not in the Italian neighborhoods on the north side of the city.

In those days, the view down south on 6th street was an uncomplicated one. When Francisco headed out in the morning to start his workday, he hitched his horse to his wagon in his barn, and made a decision about where he’d go that day. He could have turned left toward the sparkling waters of Mission Bay. Along its banks sprawled a community of les glaneurs, garbage gleaners living in ramshackle huts and making some kind of living from the city’s refuse. This area was called “Dumpville” and the Conleys lived on the edge of it. Dumpville spread over twenty acres from Channel street between 6th and 7th streets through the trainyards and wastelands of Mission Bay and was rich in raw–very raw– materials. Broken glass recovered from the site was shipped to China, and cans were smelted on the spot at a plant near Channel and 6th street.

Martin Conley and Francisco did business with this community of city miners, which formed the bottom tier of refuse collection. Both men, however, occupied the middle tier by virtue of being property owners. Francisco owned a five-room house and warehouse, and his father-in-law, who was once described as a “pedlar” in voter registration documents, declared ownership of $5,000 of real estate in the 1870 census.

“Dealing” and “peddling”, both relative descriptions, based on biases inherent in census- and self- reporting, are terms that conjure up images of itinerant, almost picaresque rootlessness. Neither word really captures the commercial or social nuance of a life supported by monetizing the city’s garbage, which is what allowed both men to purchase property–land and houses– in the city. This was the basis of real wealth and the ticket out of the environs of Dumpville.

Reselling bottles to wholesalers was probably how Francisco made his money. If he headed downtown in his horse-drawn wagon to his tin-roofed warehouse, he was there to do business with merchants in the wholesale district. His customers are now the legacy merchants of early San Francisco: Ernest R. Lilienthal who owned the Cyrus Noble Distillery, was a client and so was Arpad Haraszthy, the owner of Haraszthy & Co, and son of Agoston Haraszthy, the Hungarian who is credited with producing California’s first sparkling wine. To Haraszthy, Francisco sold his precious cache of used champagne bottles, making it possible for the family to bottle and sell their domestically produced champagne.

My energetic bottle-dealing great-great grandpa was one of many sole proprietors in the city at that time who helped develop something we like to call a “supply chain”, a mostly invisible amenity of cities (“invisible” until items like toilet paper vanish from market shelves.) In the years before the advent of the transcontinental railroad, wine and liquor merchants needed supply chains to get their hooch in a bottle and into the hands of their paying customers. But how much money was a single bottle was worth? Who knows? As of this writing, this extremely granular fact has been impossible to pin down. Business records were destroyed en masse in the 1906 earthquake, along with everything else, and so the hypothetical line item in F. Daneri & Co’s business ledger showing how much they paid my great-great grandfather for a single bottle will have to remain a hypothetical.

But I have that exact rarity: business records that survived because Francisco died in Alameda County. Neither the handwritten inventory of his warehouse or the list of merchants who owed him money sheds any light on how much he made per bottle, simply the sums of money that Haraszthy, Lilienthal and other merchants owed his estate. The inventory does show the kind and quantity of bottles that Francisco had on hand at the time of his death: 1,000 champagne bottles, among others, as valuable as a dragon’s hoard because they cost more to manufacture. Champagne bottles needed extra glass to provide buttressing against the effervescent kick of the bubbles. A bottle could cost .10 to .12 cents to make. It’s reasonable to assume a resale value of .5 to .7 cents for a champagne bottle, and maybe more.

It was harder to resell a bottle if it had a business name and address stamped on it. These personalized bottles circulated through the city, like colorful business cards. A plain bottle with no label could be resold to anyone, but merchants who paid glassworks good money– $35 to $40 dollars– to have custom molds of their names and addresses made might have been tetchy about their stuff. A name is a promise of quality and a claim of ownership. The process of buying a personalized bottle back may have been seen as something shady, like paying a ransom.

B.F. Connelly thought so, anyway. Connelly, a man who sold soda water, ran a daily ad in the North Bay papers, declaring his determination to deal directly with the appropriation of his private property. Saloon keepers and others with a steady supply of bottles would also sell to bottle dealers, who in turn sold to anyone, including their client’s competitors. If you an imagine a Hoteling bottle being sold to Francisco by a saloon keeper, who then sold it to the Cyrus Noble Distillery, you’ll have some idea of the ways in which recycling undercut bottles becoming privatized, and also a reason that bottle dealers fell under suspicion.

Paying to get your property back might have been galling, but there were other reasons to look askance at refuse dealing, like theft. Bottle warehouses and junk shops were easy places to part with ill-gotten goods. Scrap metal stripped from train yards, books, jewelry, street furniture–anything that could be carried off–were often redeemed for at least a part of their value in junk shops.

In 1871, Assemblyman Charles Goodall introduced a bill to prevent junk dealers from fencing stolen goods received from “hoodlumatic” looking young men, demanding that no junk dealer purchase anything from anyone under the age of 16, unless they were accompanied by an adult who was 21 or older and who was prepared to vouch for the provenance of the items. The state adopted his legislation, which impelled junk dealers to register all sales in a “six quarto” notebook.

Francisco fell afoul of this law in 1872 and was convicted on a misdemeanor charge for failing to “keep a record of his business purchases as a junk dealer” and ordered to appear for sentencing. This is the only time his business is mentioned in the city’s newspapers, a surprise for me. I have gotten used to seeing my other three great-great grandfathers’ businesses advertised. Francisco never ran a single ad, and after his slip up, never appears in the papers again.

In any case, glass was good to Francisco. That, and the rent he received from his house on Tehama street, allowed the Cerini family to move to Oakland, where Francisco made one of his characteristically expansive gestures by purchasing a city block bordered by Market and Myrtle streets, between 10th and 12th. He would live there for less than a decade.

Francisco’s bottle business could have been one of the enterprises that evolved into Recology, but he died of the delirium tremens in 1880, taking his dealership with him. His warehouse, which included a staggering array of bottles, including 35,000 absinthe bottles, was sold to C.J Pidwell and Co. He must have been on a daily bender for years–perhaps dealing in bottles led him to hitting the bottle. (Was drinking with his clients part of making a sale?) He was in very bad shape on May 11th, the day he or his wife Mary, whose middle name was Cassandra, summoned his lawyer and set his affairs in order. He made his last will and testament as he suffered through the seizures and hallucinations that accompany the DT’s and could only mark a shaky “X” instead of his signature. That “X” marks the spot where something of the man himself- his signature-could have peeked through the impersonal facts of his life as recorded in census records, probate documents and directory listings. He died on May 13th, at 8 pm, three days after making his will.

He was buried at St. Mary’s in Oakland, a quiet Catholic cemetery at the end of Howe Street. His estate paid nearly a thousand dollars for a 15-foot tall marble marker. This is his final resting place, and it contains multitudes, mostly Conleys: Mary and their still-born infant daughter are buried with him, as is Mary’s mother Celia, sister and brother-in-law Margaret and John Guerin, and children from her second marriage in 1883 to Nicholas Williams, a neighbor and witness to Francisco’s will.

Francisco’s untimely demise might actually have been quite timely. His death, and Mary’s marriage to Nicholas, a policeman and respected pillar of the community, allowed her to avoid the kind of fate that met other women whose husbands drank away the family fortune. Still, the site shows that his family mattered to Francisco. I think he wanted something simple and very human: to be with them. The grave and the empty bible survive as a post-mortem versions of the large house on Market street, which is long gone along with all the tensions it may have contained. For the man whose livelihood was built on glass, death came as a final, unbreakable certainty, unlike the pistol and the bottle, both only earthly defenses against life’s infinite unpredictability.

Written with love for my great-great grandfather Francisco Cerini who has always been a part of our family.

Busch, J. Second time around: A look at bottle reuse. Hist Arch 21, 67–80 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03374080

Many thanks to Eric McGuire and Richard Siri of the Federation of Historical Bottle Collectors for answering my questions and generally setting me straight about bottle resuse in San Francisco. https://www.fohbc.org/

Thanks and love to mia cara Miriam Childs, for providing accurate translations.